Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 37:2 (11-12/2013)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

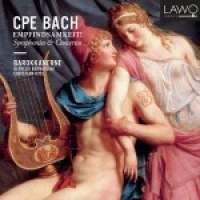

LAWO

LWC1038

Code-barres / Barcode : 7090020180397

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

Although the Norwegian period instrument ensemble Barokkanerne has been around since 1989, this is the first time that I have come across them. In 2008 they released their first disc, titled Bellezza Crudel, which was devoted to the works of Antonio Vivaldi. Since then, they have steadily developed as a group, creating a connection with the NRK, Norway’s radio and television group, and their own concert series that performs at the Cafeteatret in Oslo several times each year. This first disc was called a “treat” by James Reel in 2009 (Fanfare 32:5), and one could well hope that this was the opening gambit of a raft of discs of similar quality coming out of Norway.

With this second disc of the peripatetic composer C. P. E. Bach, the ensemble, which operates without a conductor, has demonstrated that it is truly broad in its repertory, as well as able to produce something of identical quality. Arguably the best known of Bach’s four composer sons, Carl Philipp Emanuel cut a wide swath through the music of the Classical era. His treatise on keyboard playing was seminal, and he collaborated with a plethora of major figures, beginning with his early years at the court of Frederick the Great and continuing on into a comfortable position in Hamburg as the successor of his godfather, Georg Philipp Telemann. The oft-quoted statement by Beethoven that “Bach is the father and we are his children” refers to C. P. E., and indeed the entire notion of emotion in music, the “empfindsame Stil,” may not have occurred without his guidance. Interestingly enough, only in the last decade has his music been produced in a critical edition, by the Packard Humanities Institute. This landmark musicological achievement is given a prominent place on the cover of the disc, meaning that Barokkanerne is using the latest and most authentic editions for the four works presented here.

The contents—a pair of symphonies and two concertos, one for oboe and the other for harpsichord—reflect a live concert program, but they are nonetheless well-suited to the disc. C. P. E. Bach has always been known for his eclectic sense of harmony, short, succinct themes, and his orchestration, often sort of in-your-face with high brass, skirling strings, and rapid-fire bass lines in the fast movements, and a lilting, sensuous lyricism in the slow ones. Not to make the most of this style is to relegate his music to the dull and commonplace, and careful performances are often stiff and perfunctory. Not so with Barokkanerne, which starts right out of the chute with the powerful and dramatically charged E Minor Symphony. The tempos are energetic; the playing right on the edge, especially with the swirling strings and pounding bass line; and the horns are full-throated. This is the way C. P. E. Bach needs to be played, and the woodwinds enter and depart with their momentary solo lines with ease and dexterity. In the maniacal third movement minuet, the dotted rhythms and syncopations in the inner voices provide a robust drama to the work. In the D-Major Symphony, one of four written for Hamburg, who but Bach could have started off the work with a single repeated tone, underscored by an amorphous meandering unison line in the lower strings? The music twists and turns, dodging cadential points and veering off into unexpected harmonic regions. In the lovely song-like second movement, the flutes paired with the violas offer a texture that is rich with emotion, with the pizzicato strings providing a bare skeletal musical framework. In the two concertos the same sort of drama is inherent in the music, though of course the genre requires a rather more sedate approach than do the symphonies. The Oboe Concerto, performed with a sonorous, dark tone by Alfredo Bernardini, begins with a lengthy ritornello, with the interesting inner voices of the string orchestra clearly audible, and the oboe seems to roll into its part as an integral partner rather than an aloof soloist. In the slow movement, where the minor mode is relentless throughout, the use of sighs and plaintive cries in the music reflects just that sort of emotional underlay that Bach intended. When it comes to the Harpsichord Concerto, an early work, keyboardist Christian Kjos performs the fantasy-like part with precision and subtlety, allowing for Bach’s often tortuous harmonic twists to emerge. Although these works are all examples of Bach’s well-known sensitive style, the range of drama is considerable, and I find moments of true Sturm und Drang. Again, this is the way C. P. E. Bach should be performed. The recording is infused with raw musical power and energy, and Barokkanerne has a firm grasp on both the style and the need to be edgy, just as the composer was.

Although there are a number of

recordings out there of all these pieces, for my money this is the

definitive one. Here’s hoping that Barokkanerne will continue to record

music from this period, for this disc is exemplary.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews