Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

|

|

|

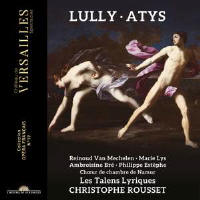

It was with Atys, staged and recorded in 1987 by William Christie and Les Arts Florissants to mark the tercentenary of the composer’s death, that the modern revival of Lully’s operas really got going. Among the participants was an astonishing array of artists who have since made their names directing performances of French Baroque music: the orchestra included Hugo Reyne, Marc Minkowski and Stephen Stubbs; Hervé Niquet was a member of the chorus. And one of the harpsichord continuo players was Christophe Rousset, who is now steadily working his way through the Lully operatic canon.

Atys was Lully’s fourth collaboration with the librettist Philippe Quinault, coming between Thésée (Aparté, 12/23) and Isis (1/20). It was lavishly staged before the court at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in January 1676, then at the Paris Opéra the following April. It soon became known as ‘the king’s opera’. The story, taken from Ovid, is told in flashback. During the sycophantic Prologue in praise of Louis XIV, the Tragic Muse Melpomene announces that the goddess Cybèle wishes to revive the memory of her unrequited love for Atys. She had sent him mad, causing him to stab his lover Sangaride to death; on regaining his wits he killed himself and was transformed by Cybèle into a pine tree.

So no happy ending for anybody; and another victim – though he didn’t die – was Célénus, the king, whom Sangaride was supposed to marry. The essential seriousness of the drama is offset by the divertissements, which give the chorus and orchestra the opportunity to shine; and shine they do, with perfectly tuned singing, the strings combined with the delicate sound of flutes and recorders. Rousset’s pacing of the score is admirable. The recitatives never drag, and the set pieces benefit from his subtle approach to tempo. In the Prologue, for instance, Flora and Time sound excited rather than merely respectful when Rousset speeds up at ‘Nothing can stop him [Louis XIV] when Glory calls’. And Cybèle’s great monologue at the end of Act 3 is all the more effective through his flexible direction.

Reinoud Van Mechelen is from Brabant in the Flemish-speaking part of Belgium, but to these ears his French sounds perfect. He is well inside the part of Atys: the heartfelt repetition of ‘If by some misfortune I should love one day …’ shows his mask slipping. Similarly, Marie Lys as Sangaride tells Doris that she loves Atys in intense recitative that really does come across as heightened speech. When Atys finally confesses his love, her pianissimo ‘Quoi? vous? Vous m’aimez?’ is heart-stopping.

Cybèle, the goddess whose descent from Olympus causes all the trouble, is the villain of the piece. But she too is a woman in love, and Ambroisine Bré evokes our sympathy in her threefold refrain of ‘Esprit si cher et si doux / Ah! pourquoi me trompez-vous?’ Philippe Estèphe as Célénus sounds properly regal and forthright at his first appearance but soon shows his vulnerability when he tells Atys of his worries about Sangaride. There is – or should be – a short comedy scene when her father appears: unlike William Christie on the pioneering recording, Rousset plays it down, Olivier Cesarini sounding rather po-faced. The highlight of the opera is the ravishing sommeil, the sleep scene introduced by strings and recorders. It’s beautifully sung by the quartet led by Kieran White; but here Christie has the edge with his more leisurely approach, taking a good 10 minutes over the first section, compared with Rousset’s eight.

The translation of the libretto comes from the Christie version, oddly attributed to a different author and repeating the line ‘Atys worships Celenus’, instead of ‘Sangaride’. Equally nonsensical, but more entertaining, is a passage in Pascal Denécheau’s essay, where the translator has evidently mistaken the name Faure (one of the dancers at the first performance) for ‘fauve’ (a wild beast), leading Mme de Sévigné to appear to have written ‘there are five or six new little men who dance like lions’.

Anyone who owns either of the excellent CD recordings listed below can rest content, but this superb performance should be the choice for newcomers. And the DVD of the 1987 Arts Flo production, which was revived in 2011, should on no account be missed. |

|