Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

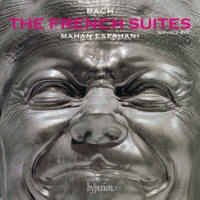

‘I became a more serious clavichord player during the first few months of the global coronavirus pandemic, which was as dark a time in my life as could be imagined’, writes Esfahani in the booklet. If the clavichord added a sense of intimacy to the earlier recording, here its more quicksilver touch has had a profound impact on the interpretation, including those works played on the harpsichord. The music feels more vocal, especially when the performer avails himself of the dynamic shading of the clavichord but also in the extension of melodic lines into more lyrical shapes on the harpsichord. Ornamentation is different, too, slightly extended for greater internal shape and nuance, rather than explosive or gestural additions to the line.

Listen to the Sarabande of the D minor First Suite, in which he deploys small decrescendos as the top line rises, suggesting not just the human voice, but the human voice doing one of its most miraculous feats: scaling down as it rises up, registering frailty, uncertainty or pleading. The more pliant ornamentation style achieved on the clavichord is sometimes carried over to works on the plucked instrument, as in the curiously forward and expanded ornamentation of the Sarabande of the E major Sixth Suite. Rhythmic articulation is often very sharp and taut in many of the livelier dances. The Gigue from the C minor Second Suite, played on the clavichord, is particularly taut and clipped, which, combined with the drier acoustic of the instrument, creates a sense of high tension. But the same nervous tension comes back in the Gavotte of the E major Suite, to similar effect. Of the ‘orphan’ suites, the inclusion of the G minor is the most curious. It’s hard to hear Bach in the rather foursquare Overture, with its not entirely successful modulation to G flat minor, though there are charming and distinctive movements that follow. ‘To make matters worse,’ writes Esfahani, ‘the G minor Suite is somewhat lacking in the infallibly golden patina characterising even the earliest of Bach’s works.’ He included it, he explains, because new evidence may some day suggest Bach’s authorship, and he would prefer to have recorded it in that case. And he finds it charming.

It is not unwelcome music – nor are the textual variants introduced throughout the nine suites on this recording – but I might have moved the G minor Suite to the end of the programme. Placed in the middle of the two-disc sequence, it will make some listeners do a double take. What is that? A beautifully played curiosity, and maybe something that Bach had a hand in, but not what you were expecting, and not quite up to the rest of the works on the recording. |

|