Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

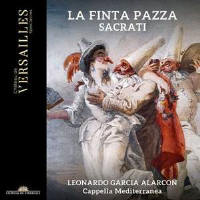

‘What Song the Syrens sang’, wrote Sir Thomas Browne, ‘or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, though puzling Questions are not beyond all conjecture.’ We don’t know for how long the librettist Giulio Strozzi ‘puzled’; but the name he chose for Achilles in La finta pazza (‘The pretended madwoman’) was Phyllis (‘Filli’ in Italian). Once you know that, it’s hard not to see the hero, slayer of Hector on the walls of Troy, in a new light. But this is to run ahead. Achilles is in hiding on Scyros at the behest of his mother Thetis (Tetide) in order to frustrate the prediction that he will be killed at Troy. Ulysses and Diomedes come to winkle him out. During his sojourn on the island, Achilles has fallen in love with Deidamia and, unbeknown to her father, king Lycomedes, has fathered a son, Pyrrhus. Another complication is that Diomedes is hoping to resume an earlier love affair with Deidamia. When unmasked, Achilles resolves to be a man and leave for Troy with the visitors. In an attempt to prevent him from abandoning her, Deidamia feigns madness. La finta pazza was the first opera composed by Francesco Sacrati (1605-50). Its premiere at the Teatro Novissimo in Venice took place on January 14, 1641: it thus preceded Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea (1643), an opera to which various composers including Sacrati are thought to have contributed. Modified versions were staged throughout Italy and, duly adapted, it became the first opera to be publicly performed in France (Paris, 1645). The score, discovered in 1984, is probably – the booklet articles are inconsistent – of one of the touring versions. The scenario mixes serious and comic scenes, the writing for the latter being distinctly fruity. The comedy comes from the Eunuch and the Nurse (Nodrice), both played by men: the Nurse advises Deidamia to go back to Diomedes, saying that she knows how to restore her mistress’s virginity. The music is in the style familiar from Poppea: recitative, arioso and aria seamlessly bound together, plus a few ensembles. The orchestra consists of a handful of strings, half a dozen continuo instruments and three players doubling on recorders and cornetts. I am not sure about the woodwind – a slightly later account book for another theatre in the Venetian State Archives lists only strings and theorbo – but their contributions are inoffensive (and very well played). The emphasis is, rightly, on the singing. Deidamia has two laments in Act 2, rather too closely spaced for dramatic balance. The second one includes a refrain, sung twice, or possibly thrice. (There is a discrepancy between what is heard and what is printed.) Anna Renzi, who created the role, went on to sing the discarded empress Octavia in Poppea, who is also given two laments. Mariana Flores sings expressively enough to persuade you, almost, that Sacrati is as good as Monteverdi. Her ravings carry conviction, and the final reconciliation duet is touching. Achilles, Ulysses and the Eunuch are sung by male sopranos: all three deliver the text with flair, as does Diomedes. Marcel Beekman, the other tenor, is amusing as the Nurse in drag. The writing for the doubled roles, as performed, is unfeasibly high, the three sopranos coming across as shrill; some welcome bass tone is provided by Lycomedes, Vulcan/Jove and the Captain. The little band plays nicely, directed from the harpsichord by Leonardo García Alarcón. The booklet is a disappointment. The libretto is given in four languages, the English version showing signs of having been translated from the French rather than the original Italian. This has led to some confusion: for instance, the excessive love to which Thetis refers is maternal, not filial; while in the introductory article, Pyrrhus is erroneously described as the grandson of Deidamia. There’s no detailed synopsis, and the scene and track numbers are transposed in the index. Despite the seemingly happy ending, Achilles sails off to his death from an arrow fired by Paris – into his heel, of course. Exactly 100 years after Sacrati, Handel covered the story in his last opera; during the same century, several composers set Metastasio’s libretto, Achille in Sciro. There’s a good DVD of Handel’s Deidamia: it’s a pity that Chateau de Versailles didn’t include one as a supplement to this attractive issue, as they did with their CD recordings of operas by Rousseau and Grétry.

|

|