Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

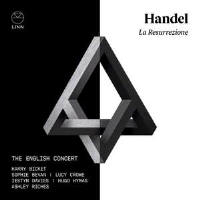

Recording of the month |

Outil de traduction |

|

Loosely based on the Gospels’ Resurrection narratives, La Resurrezione is opera by other means. In the opening scene a coloratura Angel, proclaiming Christ’s victory, spars with Lucifer, who brags and rants like a pantomime villain. The odd reference to Greek myth, as when Lucifer summons the dread powers of Hades, would not have bothered the Roman cognoscenti one iota. Matching the sumptuous setting, the 23-year-old Handel pulled out all the stops in his most ambitious and lavishly scored work to date. The invention is bold and colourful, sometimes with an inspired eccentricity. Novel instrumental effects abound. Mary Magdalene’s ‘sleep’ aria ‘Ferma l’ali’ is sensuously scored for recorders and muted violins over sustained bass pedals, while her sorrowful ‘Per me già di morire’ – the climax of Part 2 – calls for the flavoursome (and unique?) colouring of muted oboe, recorders, solo violin and viola da gamba. Among a handful of previous recordings, the standout is the excitingly theatrical performance from Marc Minkowski. This new version, with an all-British cast directed by Harry Bicket, strikes me as at least its equal. Bicket’s tempos in slower numbers – say, St John’s ruminative final aria ‘Caro figlio’ with cello solo (beautifully sculpted by Joseph Crouch) – are often a notch broader than Minkowski’s, though he never lets the music sag. His direction of the 30-strong English Concert (Minkowski’s forces number around 40) is rhythmically lively, supple, always sensitive to Handel’s often original textures. A trombone, probably used by Handel, reinforces the bass line in the arias that include trumpets. The continuo, divided between harpsichord, theorbo and organ, is inventive without fussiness (Minkowski tends to try too hard here), while Handel’s many instrumental obbligatos vie with the singers in eloquence and virtuosity. Bicket’s cast, expert Handelians all, is self-recommending. With his tightly focused bass-baritone, Ashley Riches brings a malign swagger to the jagged intervals and improbable range of Lucifer’s music, rolling his tongue gleefully round every sneering syllable. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Hugo Hymas sings with even, smoothly rounded tone as St John the Evangelist, dispenser of comfort and wisdom. Typically, he and Bicket choose a more reflective tempo than Minkowski for the ‘turtle dove’ aria, delicately coloured by flute, viola da gamba and theorbo. Both are effective on their own terms. Iestyn Davies sings the castrato role of Mary Cleophas with his familiar refined artistry, though I find him more convincing in the tragic ‘Piangete’, duskily scored with violas and viola da gamba, and the lilting ‘Augelletti’ than in the more extrovert numbers. Linda Maguire, with her stronger low register, and Minkowski conjure a more dangerous storm at sea in Cleophas’s ‘Naufragando va per l’onde’.

|

|

_small.jpg)