Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

International Record Review - (12//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

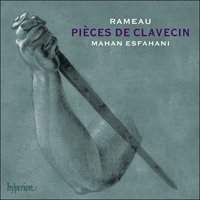

Hyperion

CDA68071/2

Code-barres / Barcode: 0034571280714

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

Since William Christie's revelatory and still exemplary recordings of Rameau's suites in the early 1980s, the great opera composer's harpsichord works have been well served on disc. A glance at my shelves reveals recordings by Ann Chapelin‑Dubar, Christophe Rousset, Blandine Rannou, Sophie Yates, Skip Sempé and, my benchmark performer in these works, Noëlle Spieth. The catalogues disclose further recordings that I have not (yet?) acquired. Several giants of the harpsichord world, such as Ton Koopman and Siegbert Rampe, have still to give us their thoughts on Rameau; and we can only hope for recordings by emerging talents such as Jean Rondeau (the seriously crazy‑haired Frenchman who impressed greatly at the recent Utrecht festival). Mahan Esfahani is a very talented young harpsichordist, who has not waited too long before diving in. Esfahani is Iranian born and studied in the United States and with the veteran Czech harpsichordist Zuzana Růičková.

Rameau began his career as an organist and his opera career actually began rather late in life. He played the harpsichord all his life and used it as a laboratory for his harmonic and other experiments. His last collection of solo harpsichord works dates from the late 1720s, but he clearly retained his skills as a keyboard performer long after. One of his rare standalone pieces, La Dauphine, was written as a musical autograph of a piece he had improvised at the Dauphin's wedding in 1747. Rameau's first collection of harpsichord works was issued in 1706, when he was 23. It is steeped in the traditions of the high‑Baroque French clavecin school, notably the works of Louis Marchand, his 1703 Second Book in particular. It even begins with an example of the venerable form of the unmeasured prelude. (I wonder if any later examples exist.) Thereafter, the suite is made up almost entirely of dance movements; however, one character piece, Vénitienne (which is a bit like a forlana in form), is a sign of things to come. In the future suites published by Rameau, all in the 1720s, character pieces came to predominate, reflecting his experience as a man of the theatre. In the later books, the influence of his great contemporaries Couperin, Scarlatti and Handel can be discerned ‑ fused with Rameau's own love of experimentation, melodic inventiveness and sense of fun. Some of his most striking pieces such as Les sauvages and La poule, both from his final Suite in G minor, have long been staples of the piano repertory too (as with much Rameau, they give the left hand a lot of interesting work to do); but this is really harpsichord music par excellence.

It is clear from his affectionate and wide-ranging booklet essay that as well as the self‑evident drama, Esfahani finds humour, irony and even satire throughout Rameau's keyboard writing. He writes little descriptions of what he imagines to be depicted in the character pieces. These sometimes whimsical and usually plausible vignettes are a useful guide to Esfahani's performance choices. I recommend keeping the booklet to hand when listening to his playing. On the whole, I found his playing delightful, intelligent and insightful. He has pleasingly clean articulation throughout and can play with muscularity or delicacy (or both) as each piece demands. His is a really impressive account of the Handel inspired Gavotte and six doubles (variations) from the A minor Suite, where he never lets momentum sag and builds up to a thrilling climax. By contrast, his Les soupirs from the D major Suite is gossamer light and seems to suspend time in dreamy nostalgia. Ravishing!

There are just a couple of mildly disappointing features, however, of this otherwise first‑rate production. First, although his phrasing is always imaginative and he certainly knows how to use a small but telling pause, Esfahani seems reluctant to add the ornaments Rameau would have expected. With many performers of Rameau's keyboard works, half the pleasure comes from hearing the embellishments (agrénents) with which they augment the music. Esfahani tends to play recurring phrases in almost exactly the same manner every time. He is a scholarly and scrupulous musician (he uses four different temperaments in the recording), so his scarcity of ornamentation cannot be inadvertent. I wish he had told us his reasons.

My second disappointment is a surprise, considering my support for historical instruments. The recording proudly features a 1636 single‑manual harpsichord by Andreas Ruckers that was converted to a two‑manual instrument in 1763 probably by Henri Hemsch. This beautiful object lives in the Music Room in Hatchlands Park in Surrey, where the recording was made. It has been recently scrupulously restored by Miles Hellon, who contributes a booklet essay about the instrument. Yet despite its impressive history, it seems to lack the deep sonorities Rameau's music so often calls for. These rich, deep hues can be heard in abundance in the recording by Rousset. But here is the paradox: that set uses two instruments, one an original built by Hemsch in 1751, the other a modern copy by Anthony Sidey and Frédéric Bal of the very same harpsichord Esfahani plays. My favourite performer, Spieth, plays a 1767 instrument by Benît Stehlin, which also boasts a much deeper resonance than Esfahani's Ruckers/Hemsch (at least as heard on this recording).

Finally, and this is a completely personal observation, I am not sure Esfahani quite has the measure of the great Allemande that opens the Suite in A minor. It is a work of extraordinary depth and concentration and I think Esfahani errs in trying to find some Ramellian irony and humour here. At the hands of Spieth, it is a work of tragic proportions, disturbing and intensely moving.

However,

these are matters that should be of interest only to other compulsive

collectors of Rameau's magnificent harpsichord pieces. Esfahani's set is, on

balance, very successful and can be recommended to diehards and neophytes

alike.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews