Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 38:2 (11-12/2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

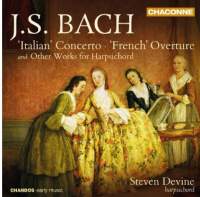

Chandos

CHAN0802

Code-barres / Barcode

: 0095115080221

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

"This is strongly recommended".

When it comes to single-disc harpsichord programs put together from a selection of Bach’s keyboard works, the choices are many; and among them, the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, the Italian Concerto, and the Overture in the French Style feature prominently in the mix, and for good reason. The latter two, though originally composed separately as stand-alone pieces, were joined at the hip when Bach published them together as Part II of his Clavier-Übung.

As for the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, it’s one of Bach’s signature pieces, and one of his most popular, though surely it’s also unique among his keyboard works. The original manuscript has been lost, but it’s believed to date from the 1720s, the same timeframe during which Bach’s interest in tempered tuning gave rise to Book I of the Well-Tempered Clavier. That makes sense, since the systemic chromaticism of the Fantasia-half of the piece—almost to the point of atonality—would not have been possible on anything other than a tempered keyboard. One can think of the Chromatic Fantasia as all 24 preludes of the Well-Tempered Clavier condensed into a single six-and-a-half-minute Dali-esque phantasmagoria.

Beyond these three frequently encountered works found on Bach harpsichord recital discs, the player has to come up with an additional two or three pieces to fill out the program, which may not be as easy as it sounds, given that the bulk of Bach’s output for solo keyboard is to be found in integrated cycles and sets—e.g., the Inventions and Sinfonias, the above-mentioned WTC, the partitas, English and French suites, and so on—and of the many isolated preludes and fugues and other miscellaneous pieces, Bach’s authorship in a significant number of cases is in doubt.

Harpsichordist Steven Devine picks a couple of works which, even if they’re not exactly underrepresented on disc, still complement the three more popular items on his program in interesting ways. The Aria variata ‘alla maniera italiana is an early work, though hardly a modest one, dating from around 1714. It’s a virtuosic showpiece from a period during which the young Bach delighted in displaying his prodigious keyboard prowess. But more significantly, Bach constructs his 10 variations, not over the work’s straightforward, chorale-like theme, but over its harmonic progression, pointing the way to the much later and more sophisticated Goldberg Variations.

The work identified and performed here as the Fantasia in C Minor is but half the loaf of the Fantasia and Fugue in C Minor, BWV 906. The problem is that the fugue-half of the loaf was never fully baked; the fire went out after 47 bars plus a downbeat. The manuscript is of uncertain date, but circa 1738 has been proposed as a reasonably good estimate. If that’s the case, the work was written during Bach’s tenure in Leipzig and is of fairly late provenance. Just as the Aria variata ‘alla maniera italiana foreshadows the much later Goldberg Variations, the Fantasia (and Fugue) in C Minor, with its slippery chromaticism and flamboyant keyboard style, echoes the much earlier Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, neatly tying Devine’s program together.

As I said at the beginning, when it comes to single-disc harpsichord programs put together from a selection of Bach’s keyboard works, the choices are many. But this new one from British harpsichordist Steven Devine is special, and not just because of its well-planned program. Devine is not a newcomer to the scene. He has played with, as well as directed, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and since 2007 has been principal harpsichordist with London Baroque. Devine’s discography, which includes his well-received debut album of the Goldberg Variations on Chandos (see Christopher Brodersen’s review in 35: 2), concentrates heavily, though not exclusively, on the keyboard literature of Bach and his late 17th- and early 18th-century French, Italian, and English contemporaries.

Unfortunately, I’ve yet to hear Devine’s Goldberg Variations, but this new release has me grasping for superlatives. I’ve heard many outstanding, not to mention some very fanciful, performances of the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, including one or two that revert to a version labeled BWV 903a, which is believed to be the earliest form of the lost original manuscript. In it, the first 20 measures are replaced by 23 measures that bear little or no resemblance to the later score we’re familiar with today.

Like 99 percent of all players, Devine opts for the well-known BWV 903 version, but I’ve never heard the fantasia’s runs played as fast and with such precise pointing as he delivers them. It’s not just a matter of velocity—that, by itself, could be achieved by almost anyone, but probably not without blurring the notes. What makes Devine’s execution so amazing is the velocity being combined with an astonishing accuracy and rhythmic exactitude, which allows every single note within the long runs to be heard individually and with equal weight and amplitude. There is absolutely no blurring or bleeding together of notes.

To no small degree, I’m sure, the perfection of Devine’s playing and the gorgeous sound he produces has to be credited to the double-manual harpsichord built in 2000 by Colin Booth of Mount Pleasant (Somerset), modeled after a 1710 single-manual instrument by Johann Christoph Fleischer of Hamburg. The keyboard is tuned to a pitch of A=415 Hz and its temperament based on Werkmeister III, which, as I’m sure everyone knows and agrees, is superior to Werkmeister II, but not as good as Werkmeister IV. The “Werkmeister” in charge of the care and feeding—i.e., tuning and maintenance—of this particular instrument is Edmund Pickering.

There is one aspect of Devine’s readings that I would question, and it pertains to his seemingly arbitrary approach to the ornamentation in the Aria variata ‘alla maniera italiana. The initial theme and a number of the variations are heavily ornamented with all manner of mordents, trills, and other squiggles which, one assumes, are Bach’s. At first, I thought I detected a pattern wherein Devine plays the first statement of each binary section more or less shorn of the ornaments, and then adds them on the repeat. But the pattern isn’t maintained in some of the variations where ornaments are indicated, but Devine doesn’t observe them on either the first statement or the repeat; and then there are variations substantially devoid of ornaments, where Devine doesn’t avail himself of the opportunity to add a few discreet ornaments of his own. I don’t want to be too critical on this point, however, because he may well be playing from a different edition than the one I’m looking at; and besides, he does take all the repeats, and his playing is of such captivating beauty that I can barely begrudge him a mordent or two.

Chandos’s pristine recording makes Devine’s playing a pleasure to listen to and one of best Bach harpsichord discs I’ve heard. This is strongly recommended.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews