Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

GRAMOPHONE (09/2014)

Pour s'abonner /

Subscription information

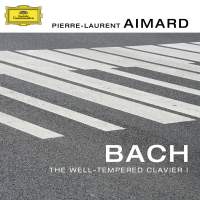

Deutsche Gramophon

DG4792784

Code-barres / Barcode

: 0028947927846 (ID469)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

Reviewer:

Stephen

Plaistow

As I’ve become better acquainted with it I’ve warmed to this recording, a little, but I know I shan’t often be revisiting it. How do you like to listen to Book 1 of the ‘48’, these 24 pairings of preludes and fugues through all the keys? In its entirety, starting with C major and proceeding to its tonic minor (C minor) and thereafter by upward semitone steps all the way to B minor? The journey takes about two hours, and of one thing we can be certain: Bach would have had a fit at the thought of our listening to The Well-Tempered Clavier in this way. For him, the volume was a resource, an exemplary collection. For his pupils it was a vehicle for advanced study, both in keyboard-playing and in composition. The two went together. A compendious achievement, it had the aim of encouraging the student to learn to play in all the major and minor keys, and in a wide range of styles, while offering to the nascent composer ‘models’, in both strict and free forms, of all the contrapuntal techniques.

Yet Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s recording tempts me to risk the observation that in some countries their reception as ‘models’, to be handed down to students at institutions along with the teaching methods of such places, has been to the detriment of a more complete recognition of Bach’s greatness. Might that not have been true in France and at the Paris Conservatoire? I hesitate to speculate further, since Pierre-Laurent Aimard is such a distinguished musician. But I do wonder, a bit: the finish in his account of Book 1 is near immaculate, if you can accept playing that never utilises the sustaining pedal and projects only the most restricted range of dynamics and light and shade. Yes, there is a little play of colour, but blink and you may have missed it. Clarity of texture and of part-playing are the virtues which predominate, plus a cool atmosphere. Whether or not we think of these as characteristically French, they do bring rewards in Bach, of course; and yet the impression Aimard conveys is of Book 1 as a monument, even a scholastic tract, in a time warp. The gamut of Bach’s rhetoric is not suggested; nor is there enough of his delight in craftsmanship and inflections of expression. I miss too a singing style and an acknowledgement of the vocal inspiration that lies behind so much of his keyboardwriting. The notes are enough, Aimard seems to be implying. Do not expect me to offer a gloss.

Best perhaps to dodge about with him, rather than take his somewhat monolithic product uninterrupted. I respond with most enthusiasm when there is variety of sound and character (C sharp major, C sharp minor, A major, B flat minor) and exceptional clarity and technical address (D sharp minor fugue, E major fugue, E minor prelude, F minor fugue). Fugue is a texture and, as we know, the character of a Bach fugal movement derives from its subject. Here, in the longest fugues, when the subject is lengthy and delineated by Aimard a note at a time, with ungenerous shaping and only vestiges of phrasing, we’re obliged to sustain ourselves with the effects of whatever build-up of inventive procedures and contrasts the composition may bring (B minor, and the A minor, which goes doggedly from beat to beat and cries out for more differentiation).

Dodge about also, if you can, in

Edwin Fischer’s pioneering recording of the 1930s, where there are wobbles and

lapses from grace but many marvels. Among modern versions I return most often to

the one by András Schiff. Peter Hill’s, on Delphian, is I daresay in danger of

being overlooked. It is intimate and he communicates as if happy to be playing

to friends. Hill is wonderful in Messiaen, as Aimard is, and I just wish Aimard

was more interested in playing Bach as lyrically as Hill does.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews