Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

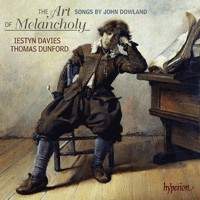

International Record Review - (07-08//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Hyperion

CDA68007

Code-barres / Barcode

: 0034571280073 (ID432)

Consultez toutes les évaluations recensées pour ce cd

~~~~ Reach all the evaluations located for this CD

John Dowland was the most flamboyantly melancholic musician of his time,

when melancholy was a fashionable condition. Some, such as Robert Burton in

his Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), ascribed many causes to, it,

including the political and religions uncertainties of the age and marked

social change. They also identified frustrated ambition (a natural

concomitant of an age of political insecurity) as another cause.

Interestingly, the difficult, tactless and mistrustful Dowland may also have

been one of the most professionally frustrated musicians in England for,

despite his international fame, almost unique for an English lutenist of the

time, it was only after many failed attempts and years of professional

(albeit well‑remunerated) exile that he finally won his much‑coveted

position at the English court.

The countertenor Iestyn Davies

believes that Dowland probably suffered from genuine depression. This

explains some of his interpretative choices in this recital; but it is

generally accepted that Dowland's melancholy was largely an artistic pose.

Dowland's contemporaries regarded sad music as, paradoxically, an antidote

to melancholy. As Burton put it, 'Many men are melancholy by hearing Musicke,

but it is a pleasing melancholy that it causeth, and therefore to such as

are discontent, in woe, feare, sorrow, or dejected, it is a most present

remedy, it expells cares, alters their grieved mindes, and easeth in an

instant.'

It is the 'care‑ and

grief‑easing' character of Dowland's songs that makes them such profound and

pleasurable listening. Davies and his young colleague, the lutenist Thomas

Dunford, have selected a rich collection of Dowland's most melancholy and

most masterful songs, including favourites such as Flow, my tears and

Sorrow, stay. Their recital demonstrates once again that, although

Henry Purcell was a more universal musical genius, Dowland surpassed him as

a song writer.

Davies and Dunford open with

Sorrow, stay and close with Now, oh now I needs must part

and the ordering of the rest of the songs reflects their thoughtful

approach. As heard already in recent recordings, Davies's vocal technique is

impressively secure (especially in the long‑breathed, almost suspended

phrases Dowland so loved) and lie overcomes a certain lack of tonal variety

through intelligent phrasing and articulation. Occasionally, his fluttery

vibrato on some notes is a little unsettling, especially after lengthy

lyrical passages of unwavering purity, but these moments hardly detract from

his refined and delicately shaped performances. The one song in which lie is

not quite successful is the most famous, Flow, my tears. His

is a rather maudlin rendition, perhaps resulting from his views about

Dowland and depression.

Another welcome feature of

Davies's singing is ornamentation, which is a comparative rarity in Dowland

song recordings. He generally confines his embellishments to the strophic

songs. Just occasionally, such as in the last verse of Come again,

lie sings an unidiomatic trill that sounds more like Porpora than Dowland,

revealing that, despite the polish of his performances, his journey of

discovery of Dowland has only recently begun.

Dunford, for his part,

combines in his lute playing an enviable technical facility and an artistic

insight beyond his tender years. His handful of solos on the disc, as much

as his song accompaniments, are models of precision allied with incisive

emotionaI perceptiveness. At the centre of the programme lie plays a solo

longer than any of the songs, the punningly emblematic Semper Dowland

semper dolens ('Always Dowland always mournful'), with flawless control

and heartfelt expression. Equally impressive is his account of the

emotionally complex Lachrimae and the rather jollier Mrs Winters

Jump.

However, it

seems Dunford has selected a very unorthodox instrument for this disc. No

explanation is provided in the booklet, which merely describes his

instrument as 'lute'. His photograph shows him holding what appears to be an

archlute, a larger form of the instrument whose range in the bass was

extended by the addition of unstopped strings attached to a long neck

extension. It seems this is the instrument he uses on this disc, since its

unstopped bass strings can be heard resonating sympathetically as he plays

and it has a brasher and longer‑sustaining sound than a conventional

double‑strung seven or eight‑course lute of the kind Dowland would have

used. In the hands of a less skilled player, this could have resulted in an

imbalance between voice and lute. Thankfully that is not the case here,

although this choice may surprise lute fans.

The sound quality of the

recording, made in Potton Hall in Suffolk, is exemplary in its clarity and

naturalness. For this review, in addition to the physical disc, Hyperion

provided the high‑resolution (24 bit, 96 kHz) 'studio master' download

version in FLAC format available from its website. Played on my hi‑fi

system, this version located the musicians more clearly within the recording

space and heightened especially the immediacy of the lute, although the

difference is subtle.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews