Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

International Record Review - (07-08//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

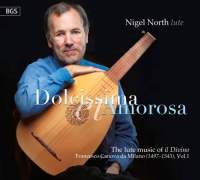

BGS

BGS122

Code-barres / Barcode : 0680569884596

Every lutenist recording a disc of the music of Francesco Canova da Milano (1497‑1543), nicknamed 'the Divine One' by his contemporaries, is required to recount the French priest and poet Pontus de Tyard's famous description of the composer's near-Orphic skill while playing during a banquet attended by Jacques Descartes in Milan. Nigel North is no exception: his well‑written and informative booklet notes quote the whole passage by Tyard, who described Francesco sitting on the edge of one of the tables cleared after dinner and playing with such ravishing skill that, with his first notes, he stopped all conversation and then held his audience spellbound, seemingly paralysed and deprived of emotional control and all senses save hearing, until he finally released them. Tyard was not an eyewitness and his description, which post‑dates Francesco's death by 12 years, may owe something to his own neo‑platonic theories about divine artistic inspiration (or fureur poétique) and its close relation to madness. However, Francesco's contemporaries' universal admiration of his artistic skills and the extraordinary quality of his extant lute music suggest Tyard's account is not completely fanciful. Moreover, other stories from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries of lutenists with a similar power indicate that our pre‑electronic‑age ancestors' listening habits were vastly different from ours.

As both Paul O'Dette and Hopkinson Smith did on their most recent da Milano discs, North presents five 'suites' of Francesco's fantasias and ricercars with which he intends to stir our emotions, especially our amorous ones as the disc's title implies. The Fantasia 'Dolcissima et Amorosa' is an excellent example of what makes Francesco's music so captivating, for it fuses together effortless counterpoint, passages of chanson‑like tunefulness, rich harmonies and an almost improvisatory-sounding profusion of ideas. North has included only two of Francesco's sublime song intabulations in his recital: Jacques Arcadelt's madrigal Quanta beltà and Jean Richafort's De mon triste de desplaisir. The melancholic latter may have had almost an emblematic significance for the composer since, as North points out, not only did Francesco also write a whole separate Fantasia 'De mon triste' but segments of this Franco‑Flemish chanson pop up in several of the pieces on the disc, including the often‑recorded La compagna fantasia.

There are many strengths in North's performances on this disc. He is especially successful in bringing Francesco's counterpoint to life, distinguishing clearly between the voices, as well as in bringing out his melodic ideas, some of them mere hints thrown up and then almost immediately obscured in the composer’s continual play of light and shade. Yet, North's renditions, although fluent and beautiful, do not quite match the quicksilver lightness of O'Dette or his depth of expression. Like O'Dette, North favours a considerably brighter and more robust tone (heightened by his high pitch of A=440) than Smith's, which is usually quite soft‑edged; but he tends to play much louder, as if to a large concert‑hall audience, rather than sitting around the centre of the instrument's dynamic possibilities. This means that when there is a crescendo or a strong note, he seems to have little room to move dynamically and, especially in the case of the chanterelle (the top string), comes close to plucking it at the absolute limit of its loudness. (This is more disappointing when listening to this disc through headphones, my favourite way of listening to Renaissance lute music, than on loudspeakers.) As a result, he misses some of the poetry and emotional mystery that O'Dette, with his quieter playing, manages to elicit from the music despite his generally faster speeds. But only some. Overall, this flaw is of relatively little significance because North's renditions are masterful, not least owing to his polished phrasing (with none of Smith's disconcertingly changeable tempos) and impeccable voice‑leading.

Oddly, despite being recorded in the large neo‑Gothic St Andrew's Church in the tiny village of Toddington, Gloucestershire, North's acoustic ‑ like Smith's, in a French chateau ‑ sounds considerably less 'churchy' than O'Dette's, an apparently large and very empty concert hall. A note in the booklet (welcome because so rare) states that North's six‑course instrument, based on early sixteenth‑century Venetian models, is tuned at the modern standard pitch of A=440, but in sixth comma meantone temperament, a softer version than the more usual quarter comma meantone.

This

disc is the first of a planned three of Francesco da Milano by North on the

British Guitar Society's label. The rest of the series certainly will be

worth waiting for.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews