Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Trčs approximatif) |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

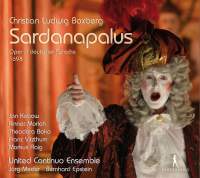

Brenesal I received this opera for review days before one arrived that had been composed by the celebrated Reinhard Keiser—the irony being that Christian Ludwig Boxberg (1670–1729) and Keiser were classmates who graduated from St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig in 1693. The subsequent trajectory of their careers also has its element of irony, as Keiser’s took him to Hamburg’s Gänsemarkt Oper (the first civically maintained opera house in the German States), which had been founded by Nikolaus Strungk; while Boxberg went to the Leipzig Opera, performing as a singer directly under the direction of Strungk. Here, the similarities cease. Hamburg gave Keiser great control over opera, for all that the quirks of its culture made a hash of librettos, while Strungk preferred to remain the sole operatic composer in residence in Leipzig, utilizing Boxberg’s considerable talents as a singer and librettist. It wasn’t until Strungk was sunk under an avalanche of debt that Boxberg got his chance. Things were looking up for him, when a dispute broke out over rights ownership between the opera house’s architect and Strungk’s descendents. The young composer sided with the architect; Strungk’s family won the legal proceedings; and Boxberg, deprived of a living, took up the post of organist in Görlitz, while attaching himself to the court of Ansbach. The Leipzig Opera sent out a troupe to Ansbach in 1697, where the youthful Margrave Georg Friedrich II was known for his encouragement of the arts. However it was managed, Boxberg and the Strungk family made up their quarrel, and the company produced at least two operas set to music and text by Boxberg. One survives: Sardanapalus, in a fair-copy score, presumably owned by one of the singers, tenor Andreas Luther, who was Strungk’s son-in-law, and whose handwriting is apparent in numerous additions to the work. The Margrave paid the Italian singers and instrumentalists he’d enticed to his court salaries considerably in excess of his native German musicians. Whether this factored into the musical style of Sardanapalus or not, it is heavily Italianate. The liner notes call it “the fluent modern, Italian operatic style,” but then doesn’t go into any details; which is just as well, since the work is extremely conservative, owing less to Scarlatti than Cavalli. Extremely short da capo arias, often in three syncopated beats, predominate. Bass lines are functional harmonically and with few exceptions, little else. Short introductory orchestral passages are common, and the singer’s thematic material is sometimes echoed, but instances of instrumental color are almost non-existent. Compared to Keiser, Boxberg was writing in a much older style, and it was presumably one Georg Friedrich preferred. In keeping with court tradition, the dances were under separate, Italian direction, their music taken from large collections of ballet music composed over decades by Gregorio Lambranzi and Nicola Matteis the Younger. The German recitatives and arias are fluid and not infrequently eloquent, in a way that Keiser might surely have wished on some of his operatic collaborators. But the plot is pre-Reform at its worst, with various disguise exchanges that are instantly perfect, and eight (out of 10) mostly noble characters whose actions are governable only by their tangled, ever-shifting loves and misdirected jealousies. The recording was made live, and apparently represents an amalgam of a pair of performances given in February 28 and March 1, 2014 at Wilhelmatheater, Stuttgart. (Judging from the pictures, there were no stage sets or furnishings, and very stylish costumes, makeup, and gestures.) I mention this first because the problematic engineering definitely has an impact on my perceptions of the singing. The microphones favor the instruments, being closer; and they sound both colorful and robust, if a little boxy. The singers, depending on stage position, are at a slight to moderate distance from the mikes, inevitably losing some tonal quality, and suffering from a cavernous acoustic. It’s possible to adjust mentally for at least some of this, but it can’t be said to make for extremely pleasant listening, nor to cast the performers in the best light. There are even moments when some of the singers briefly vanish beneath the instrumental ensemble of just seven players, as during Sardanapalus’s sneering “Mit eurer Hand, ihr mutigen Soldaten.” No one apparently thought to consider that a stage makes a single visual unit to the listener however it is divided, but many discrete audio ones with narrow or broad borders; and that a performer facing upstage, or moving across it, may change volume, resonance, and tonal depth depending on how well the recording is made. Ideally, the United Continuo Ensemble would have been brought into a studio where constant balances could have been better achieved in a good, close acoustic environment, and cosmetic touch-up applied in a separate session for little orchestral and vocal flubs. With all that noted, I found the cast to be a good middling one. Everybody has a sense of the proper style, and most enunciate well. Standouts include Markus Flaig, who manages figurations cleanly in the lower part of his voice (but scrambles in the upper notes), and Jan Kobow, whose occasional shortness of breath doesn’t preclude attention to note values and expressiveness. Franz Vitzthum is one of the best countertenors I’ve heard in years, with fine coloratura, and attention to dynamics in his defiant “Kein Qual soll mich erschrecken.” Perhaps best of all is Rinnat Moriah, whose delicate soubrette soprano easily navigates the upper reaches (with a fine trill) of “Liebe lässt sich nicht erzwingen,” yet is capable of sweetness and excellent phrasing in “Drücke die grebrochnen Augen.” It’s admittedly difficult to get a full sense of the voices here, because in numerous cases chest resonance is almost completely missing thanks the recording, but it’s clear there was a good deal of above-average singing and playing when this Sardanapalus was made. Bernhard Epstein leads an energetic, focused reading that is sensitive to his soloists. Is this worth the purchase? I can’t honestly see Fabio Biondi, Alan Curtis, or the good folks at the Boston Early Music Festival doing Sardanapalus anytime soon, so despite my moderate qualifications about some of the singers and greater qualifications about the sound, I’d give a tentative nod to it. However, you may feel otherwise when you find out that the text is only supplied in the original German. I can’t understand the reasons for that. At the very least, Panclassics should have provided text and translations online, where it wouldn’t have cost anything to print. As it is, they’re cutting into their revenues here in a nation where many people are monolingual (and, some would argue, not even that). My thumbs-up remains, but the choice is yours. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|