Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

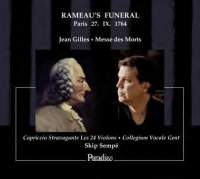

Brenesal It would be difficult to overestimate the popularity of Jean Gilles’s Requiem. Shortly after his death, the work took hold in France, leading to more than a dozen arrangements appealing to all classes, tastes, and costs. It was subject to all manner of revisions. Tempo indications, scoring, instrumentation, new harmonies, and freshly composed insertions made their way into the score. Gilles died in 1705, but his Requiem spawned a publishing cottage industry that spanned the 18th century. Among the famous whose deaths were honored with this work was Rameau. It was an extremely formal, official affair, held at the Rue St. Honore on September 27, 1764, with over 1600 invited guests in attendance. (The state’s absorption of the cost would have raised a chuckle from the composer, whose acquaintances and final inventory suggest he became miserly in his old age.) Sempé reasonably suspects that the arrangement employed at his funeral was made by the composers and lifelong friends, François Rebel and François Francœur, whose skill at organization was widely respected in Paris: They acted as joint music directors of the Paris Opéra for many years, when it was a rat’s nest of conspiracies and factions. (It was not the Requiem arrangement by Michel Corrette, sometimes confused with that heard at the funeral because it was published in the same year.) The work was updated for Rameau not only with a range of extra instruments—horns, bassoons, oboes, contrabass, muted timpani—but also with additions from Rameau’s operas, treated as contrafacta with new texts. So although no motets are included between Mass movements, the latter two-thirds of the Kyrie employs the starkly tragic chorus, “Que tout gemisse,” from Castor et Pollux. (A third service, held on December 16, used more extended passages from that opera in a De Profundis.) That leads in turn to an impressive orchestral movement drawn from Dardanus. The Graduel II returns to Castor for “Séjour de l’eternelle paix;” and “Tristes apprêts” followed the Sanctus. The Elévation (sung to the Pie Jesu text) employs an aria by Domenico Alberti, curiously enough, and completely out of style with the rest. The expansive liner notes are strangely silent over two concluding orchestral movements tacked onto the Requiem, drawn from Dardanus and Zoroastre respectively, which leads me to wonder whether they weren’t simply arranged for this recording by Sempé himself. They steal the program’s focus away from religion, but they improve the disc’s short timings; and it’s difficult to imagine the composer’s spirit wouldn’t have been pleased with the exhilarating Air des esprits infernaux that concludes the concert, entitled here, “Apothéose de Rameau.” The performances by Capriccio Stravagante under Sempé’s baton are uniformly excellent, well disciplined and appropriately paced. Judith van Wanroij, whom I greatly enjoyed in Pirame et Thisbè by Rebel and Francœur (Mirare 058), is a bit dark-toned for the soprano part—at least, as recorded here in Bruges’s Sint Walburgakerk—but supremely focused and with plenty of voice in the Elévation to fill the church. Robert Getchell, whose enunciation I praised in Lully’s Bellérophon (Aparté 4625), is less hard of tone here, and manages the Graduel II gracefully. Juan Sancho is perhaps not as effective in managing large intervals, but Lisandro Abadie is appropriately majestic in his solo at the start of the Offertoire. The sound, while resonant, never becomes burdened with the sonic slurring so common to smaller ensembles, poorly recorded in cathedral venues. Latin texts are supplied. This admixture of Gilles and Rameau works well. The orchestrations supposedly provided by Rebel and Francœur are tasteful, lacking the vulgarity of Corrette’s carillon. All in all, this is a highly successful recording of a work whose arrangements number over a dozen. Recommended. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|