Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

| "Very strongly recommended." |

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Jerry

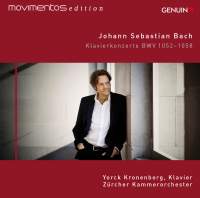

Dubins Tilmann Böttcher’s album note tells us nothing we don’t already know about these seven concertos. Bach arranged them to be played at Zimmermann’s Café by the Collegium Musicum, a community orchestra originally founded by Telemann. The concerts took place once or twice a week and were not the intimate affairs imagined by the one-to-a-part enthusiasts. The orchestra was made up mainly of students from the university, amateur players from among Leipzig’s citizens, and a few professional ringers to take some of the more difficult solo parts. The hall in which the performances took place is said to have seated an audience of 150 and the concerts were so popular and well attended that Zimmermann grew rich sponsoring and supporting them. In the summer months, the concerts were moved outdoors to accommodate even larger crowds. It’s reported that Zimmermann was so keen on promoting these concerts and encouraging still more players to join in that he even offered to supply the instruments. Yet despite all evidence to the contrary, the “flat-earthers” will still try to convince you that these were occasions for no more than four or five players. Two of the keyboard concertos—the G Minor, BWV 1058, and the D Major, BWV 1054—are obvious arrangements of two already extant violin concertos, respectively, the A Minor, BWV 1041, and the E Major, BWV 1042. Why Bach went to the extra trouble of transcribing each of them down a whole step is anyone’s guess. In any event, since orchestral concertos featuring harpsichord as the solo instrument do not figure in Bach’s output prior to these Zimmermann Café concertos, it’s conjectured that four of the remaining keyboard concertos were also arranged from previously existing works for other instruments. The source for the D-Minor Concerto, BWV 1052, is believed to be another violin concerto; while the source for the A-Major Concerto, BWV 1055, is believed to be a concerto for oboe or oboe d’amore. The problem is that the presumed original scores are lost. Provenance of the E-Major and F-Minor concertos, BWV 1053 and 1056, is even sketchier, for they seem to have been cobbled together from pre-existing unrelated works, rather than from pre-existing complete concertos. The only concerto among the seven that more or less retained its original solo parts is the F-Major Concerto, BWV 1057, which features harpsichord and two recorders. But this concerto underwent the most radical change of all, for while it kept two of its three soloists, it was subjected to what might be considered the musical equivalent of a sex change operation. In its original form, it’s the Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major, BWV 1049. But in transforming it into the Concerto in F Major for Harpsichord and Two Recorders, BWV 1057, not only did Bach transpose it down a step, he converted it from a concerto grosso to a solo concerto. You need only look at the scores of the two BWV numbers to see the before and after. As the Brandenburg Concerto, the score contains parts for a violino principale and the two recorders, which comprise the concertino group, and then parts for violino I di ripieno, violino II di ripieno, viola di ripieno, cello, violone, and continuo. As the Concerto for Harpsichord and Two Recorders, BWV 1057, the violino principale part is dispensed with in favor of a normal violin I part, and in place of the ripieno parts, we now have typical orchestral concerto parts for violin II, viola, cello, and violone, the latter two together now designated continuo, while an added cembalo part beneath them functions as both the third solo instrument with the two recorders, as well as simultaneously supporting the continuo. Bach had to do some major reworking to accomplish this gender bender, reassigning the virtuosic solo violin part to the harpsichord, and remaking a concerto grosso into what was effectively a triple concerto. It’s in this concerto that Yorck Kronenberg switches from piano to harpsichord to join recorder players Laura Schmid and Claudius Kamp. For all the other concertos Kronenberg plays a magnificent-sounding Bösendorfer concert grand; and I have to admit that although I’ve tended to prefer hearing these works on harpsichord, that preference has not been due to a disinclination on my part to hearing Bach on the piano. To the contrary, I would have happily embraced a set of these concertos on piano if I’d ever heard one that I found completely satisfying. But, until now, I haven’t. The few complete sets I’ve heard have disappointed, either because the performances didn’t strike me as being particularly informed of period style and historical practices, or the recordings suffered from a lack of clarity and detail. The latter was my complaint about Vladimir Feltsman’s set on Nimbus with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s and Decca’s reissue of its 1990s set with András Schiff. These performances by German pianist and composer Yorck Kronenberg are really excellent—mindful of historical practice, and alive to the rhythmic verve that pulses through the concertos’ outer movements and to the singing lines that Bach spins out in the middle movements. Kronenberg adds minimal ornamentation, and when he does, as at cadential flourishes, it’s modest, tasteful, and fitting; and, as noted above, his instrument, a Bösendorfer concert grand, is blessed with a rich, deep voice and firm bass, but one that lets sufficient light through to allow Bach’s counterpoint to shine. To no small degree, the success of these performances must also be attributed to the venerated Zurich Chamber Orchestra of Edmond de Stoutz fame, the conductor who founded the ensemble and led it for 51 years, from 1945 to 1996. Its present conductor, since 2011, Roger Norrington, has shared with the orchestra his own years of experience and knowledge of period performance practice, which further explains the exceptionally alert and stylish orchestral playing, led here from the concertmaster’s chair by Willi Zimmermann (any descendant, I wonder of the Zimmermann Café’s proprietor?). Recorder players Laura Schmid and Claudius Kamp are superb as well in BWV 1057. Very strongly recommended. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|