Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

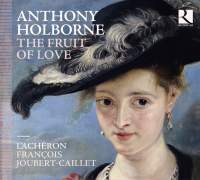

Brenesal In his day, Anthony Holborne (c. 1545–1602) was a highly respected composer and instrumentalist. His patrons included Robert Cecil, the first Earl of Salisbury; Mary Sidney, Countess Pembroke; and Elizabeth I. He wrote dedicatory introductions to publications by Thomas Morley and Giles Farnaby, and Dowland dedicated his song I saw my lady weep to him. Upon Holborne’s death he was quickly forgotten, as were many of his contemporaries, only to experience a considerable revival in the 20th century. Today his music is often recorded in excerpt as part of larger collections, but occasionally in releases devoted entirely to his works. One of Holborne’s pieces, The Fairie Round, was part of the so-called Voyager Golden Records sent with space probes Voyagers 1 and 2, to represent the cultural achievements of humanity. It was part of the composer’s 1599 publication Pavans, Galliards, Almains, and other short Aeirs both grave and light, in five parts, for Viols, Violins, or other Musicall Winde Instruments. This was to be his only published music not written for solo plucked instruments and, at a total of 65 dances, a very large collection for its time and place. Many of the works are given titles, some clearly drawn from songs, but 53 are either pavans or galliards—the majority of these in paired association. The music thus alternates between the more stately and the more lively, though Holborne’s excellent five-part writing makes it clear these pieces were intended more for listening pleasure than actual dancing. Publishers of the day realized they could make decent money off the sale of music to a thriving middle and upper class, at a time when music-making was both an important element of private entertainment and a marketable skill to attract good marriages. To maximize sales, composers often indicated that their works could be performed by a wide range of instruments. Holborne’s title above indicates as much, and François Joubert-Caillet takes his cue from this. L’Achéron opts here for a traditional viol consort, abetted by a pair of musicians on plucked string instruments that Holborne was known to specialize in: the lute, cittern, and bandora. Finally, they’ve included the very occasional use of a virginal and ottavino (small spinet). While keyboards aren’t mentioned by Holborne, they are in other sources of the period, and they’re deployed with discretion—most obviously, and to excellent effect, as a solo in the opening statement of Paradizo—and a combination of plucked instruments and ottavino alone perform an unnamed Almain of obviously Italianate origin. Mention of this brings to mind that other recordings prefer different arrangements. Jordi Savall and Hesperion XXI (Alia Vox 9813) give a greater role to lutes, and Pedro Estevan adds a bit of light percussion in such pieces as The Honie-Suckle. Skip Sempé and Capriccio Stravagante (Paradizo 1) opt to mix viols and solo flute, with generally good results. I would place L’Achéron squarely between these two as a balance of dance and abstract listening. Savall clearly wishes to emphasize the dance aspect of Holborne’s music, while Sempé focuses less on rhythms than on rich textures and, at times, almost Romanticized dynamics in the phrasing. Joubert-Caillet is a bit slower than either in many instances, but with more forward impetus than Sempé. Those three versions are my current favorites; and if I had to choose, this would be my preferred one, with close, richly textured sound. But only by a hair over Savall; so if you have that one, you’re probably good to go. If not, however, I strongly recommend this recording. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|