Reviewer: John

W. Barker

Librettists and composers have

been drawn, almost from the origins of opera, to the story of Armida (Armide)

as told by Tasso in his Gerusalemme Liberata: the Saracen sorceress who

enchants and distracts the crusader hero Rinaldo (Renaud), actually falling

in love with him, but then losing him to the call of duty when he comes to

his senses. Lully’s setting of the story was among the earlier ones, if by

no means the earliest. It dates from 1686, a year he died, and served as the

crown on his creation of the French tragedie lyrique. With his librettist,

Philippe Quinault, Lully short-changed the details of the Armida-Rinaldo

alliance and concentrated strongly on Armida herself and the terrible

ambivalences she suffered. Should she kill this Christian warrior who was

her enemy, or should she succumb to her attraction to him? How can she cope

with his seemingly quick disenchantment and determination to leave her? (For

his part, how does he deal with his rediscovery of duty and his sympathy for

her abject state?) As first represented in the Prologue, the story is

plainly characterized as the triumph of duty over love. (At the same time,

Act IV—too often cut or reduced—is supplied for comic relief, as two of

Renaud’s buddies cope with magical obstacles.)

This is the opera’s fourth recording. Of the predecessors, the most recent

was one organized by Ryan Brown with Opera Lafayette (Naxos 660209, 2CD: M/A

2009). His cast of young singers, mostly American, sing a creditable

performance, with Brown working hard at creating a French Baroque sound. But

needless cuts were imposed, and that effort was just not up to the standards

of two earlier recordings, both led by Philippe Herreweghe. His first

recording was released in 1984 by Erato (not reviewed): though highly

artistic, it was marred by heavy cuts. He returned to the opera for a staged

production in 1992, and a byproduct of that was his second recording (Harmonia

Mundi 901456; S/O 1993). That recording was a superlative example of

stylishness and dramatic strength, with a starry cast led by Guillemette

Laurens, Howard Crook, Veronique Gens, Bernard Deletre, and Giles Raglan. As

a supplement to the audio history, there is a video documentation of a 2008

staged production under William Christie (Fra 7: N/D 2011). That performance

is superlatively artistic and idiomatic, but things are ruined by William

Carsons’s utterly reprehensible staging. If only the audio dimension could

be issued on CD we would have a really important competitor.

The second Herreweghe

recording becomes the yardstick, but it is deleted for now.

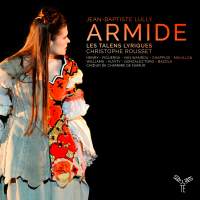

Rousset, absolutely no slouch in French Baroque music, may be the one to get

as of now. His recording competes head-on with Herreweghe II and achieves an

impressive parity. The role of Armide is a wonderful vehicle for

histrionics, and its previous portrayers have all been striking. With a dark

soprano coloring, Henry can convey powerfully the range and depths of

Armide’s emotions, sometimes verging on hysteria; it is a gripping

characterization. Surpassing Herreweghe’s Crook, Figueroa offers a lean

tenor sound very much in the French mode and suggests a true hero out of his

normal world. Auvity and Bazola are fine as the clumsy buddies. Mauillon is

scary as the foiled meanie Hatred (La Haine). Though I have not listed them

above, I must commend sopranos Judith van Wanroij and Marie-Claude Chappuis,

who sing elegantly a number of small roles—there are 14 roles in all. The

chorus of 20 and the orchestra of 28 make strong and satisfying

contributions. Rounding out the admirable musical dimensions is a handsome

package, in boundbook album, with good notes and full French libretto with

English translation.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

|