Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Christopher

Price We are all familiar with stories of the cruelty of dissolute and capricious Roman Emperors. For the citizens of the Roman Empire, however, it was the mythical Assyrian king Sardanapalus who was the exemplar of the evil and depraved tyrant. The wholly fictitious Sardanapalus perfectly fitted the Roman stereotype of the indolent, pleasure‑loving, cowardly and effeminate Oriental despot. According to Graeco‑Rornan legend, his obsession with luxury, his huge harem of concubines and eunuchs, and with dressing as a woman and wearing whitening cosmetics caused the fall of Assyria in the seventh century BC.

Both the libretto and music of Sardanapalus were written by Christian Ludwig Boxberg (1670‑1729), who had made a reputation as the librettist for many of the operas that Nicolaus Adam Strungk (1649‑1700) composed for the civic opera bouse he had opened in Leipzig in 1693. As Strungk's right‑hand man, Boxberg was only rarely allowed to compose operas. In 1698, the Leipzig opera company, minus the heavily indebted Strungk, who was hiding from his creditors, travelled to Ansbach and performed two operas by Boxberg for the music‑loving Margrave Georg Friedrich. The survival of the score and libretto of Sardanapalus makes it the earliest extant German‑language opera from Central Germany.

It may seem surprising that a late seventeenth‑century German opera would feature such an unsavoury character as Sardanapalus, particularly when composed not as a public entertairiment but for a prince. However, as the god Mars explains in the prologue, seeing the vices of so ignoble a character can teach us (and presumablv especially the Margrave) to recognize true virtue. That flimsy excuse and a jolly chorus singing the praises of the Prince out of the way, the opera unfolds as an unabashed comedy. Sardanapalus's first aria, 'Wer bei steter Arbeit schwitze', arguing that pleasure is more important than work, sets the tone. After much scene‑setting in Act 1 (Sardanapalus has deféated his enemies, Arbaces and Belesus, and captured the latter's son, Belochus, who falls for the Assyrian princess Agrina ‑ who in turn loves Arbaces ‑ and is beloved by two other desperate Assyrian princesses, Didonia and Salomena, the latter of whom has unknowingly smitten Sardanapalus's unhappy servant, Saropes), Act 2 unfolds in Sardanapalus's seraglio. There, the king, in female dress, simultaneously catches the eye of and is attracted to Arbaces's servant, Atrax, who is himself disguised as a woman and trying to find Agrina in the harem. Atrax's passion is quelled, however, when he finally kisses Sardanapalus and feels his stubble. He then flees with the help of Agrina's page, Misius, and dons the escaped Belochus's ' discarded clothing (for Belochus too, freed from his dungeon by Didonia, has disguised himself, though not as a woman); but he is mistaken for Belochus, imprisoned and then subjected to the deceived Salomena's amorous advances. Meanwhile, Arbaces has also crept into the seraglio, disguised as a Moor, resulting in further comedy of errors when he sees Belochus in close, though innocent, conversation with his Agrina.

Act 3 sees Sardanapalus foolishly ignoring the danger of his enemies' arrny at the gates of Nineveh while lie indulges extravagantly in his pleasures, then suffering defeat and, to avoid the shame of capture, having himself immolated with all his women, eunuchs and possessions on a huge (offstage) bonfire. The opera ends with a resolution of the complex love polygon between the other characters.

Unfortunately for non‑German speakers, no translation of the libretto is provided, a significant drawback for a recording of an unfamiliar, dense‑plotted Baroque opera. However, a comprehensive synopsis ensures Anglophone listeners are not left entirely in the dark.

The performance, recorded live in the modest and acoustically dry early nineteenth-century Wilhelma Theater in Stuttgart in early 2014, is light‑hearted while avoiding any heavy‑handed underlining of the comedy, which would be quite unnecessary with such a farcical plot. The sound engineers have successfully captured the theatrical atmosphere of the venue, stage noises are audible but not intrusive and the sound is clear ‑ though the acoustic is a little unforgiving for the voices.

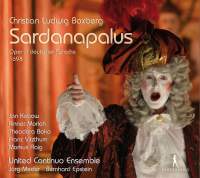

Tew digipak and booklet include photographs of the production in a small Baroque style theatre in Gotha, showing the characters in sumptuous period costumes (possibly tweaked, to my untutored eye, by modernist touches), singing with appropriate gestures amidst period stage scenery, a rare sight indeed in modern Baroque opera productions. There are also individual full‑length photographs of the six main characters posing in their theatrical costumes and make‑up.

Such a production merits praise; but, unfortunately, it is marred by some disappointing singing despite some fine contributions and the excellence of the period‑instrument United Continuo Ensemble (harpsichord, theorbo, Baroque guitar, harp, cello, violone and bassoon) and its small guest orchestra of two violins, viola, three oboes, recorder, four trumpets and timpani. The tenor Jan Kobow is quite effective as the dissolute Sardanapalus, but the dry acoustic exacerbates the harsh edge to his tone and he too often applies a pronounced vibrato that disrupts his musical line. No such problems bedevil his fellow tenor Sören Richter (Atrax), who achieves a nice balance between his role's cornic requirements and vocal polish ‑ and his cross‑dressing falsetto manages to sound at once attractive and unaccustomed. Most unsatisfactory are the two principal sopranos, Rinnat Moriah (Salomena) and Cornelia Samuelis (Didonia), and the mezzo Theodora Baka (Agrina). They make little attempt to conform to an historically apt Baroque vocal style or delivery, forcing their voices in the modern operatic manner and employing far too much vibrato (though less than one encounters in productions of Romantic period and post‑Romantic operas). By contrast, the singing of the countertenor Franz Vitzthum (Belochus) and the bassbaritone Marcus Flaig (Arbaces) is delightful. Also excellent is the bass Felix Schwandtke as Belesus.

Musically, Sardanapalus is at some remove from the more familiar style of Handel and his contemporaries and rivals. There are no large‑scale arias: rather the work unfolds in a series of very short recitatives, ariosos and arias, with the occasional brief vocal duet, trio or quartet. There are over 45 arias, none longer than three minutes. These are generally attractive and melodious, and some stand out especially, such as the busy ostinato‑based Act 1 Scene 5 aria of Belesus, 'Keine Qual soll mich erschrecken", Agrina's 'Melde doch, wie soll ich lichen' (Act 2 Scene 18) and Sardanapalus's farewell aria in Act 3, 'Ihr grausarnen Himmel'. Boxberg's music is supplemented by some stylishly performed orchestral dances, marches and chaconnes bv Nicola Matteis (c.1670‑1737) and Gregori Lambranzi (active around 1716).

Despite its flaws, this an interesting recording for the Baroque opera enthusiast.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|