Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Barry

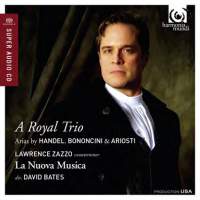

Brenesal In his biography of Handel, Paul Henry Lang quotes Chrysander on the division of operatic content during The Royal Academy’s activity prior to its collapse in 1728. Of 428 operatic performances, Handel’s works were represented 245 times; Bononcini, 108; Ariosti, 55; and all others, 79. Lawrence Zazzo didn’t come to the idea for an album devoted to the Academy’s operatic triumvirate from Lang, but according to his release notes, from very favorable contemporary comments about Bononcini and Ariosti. The Handel revival has done little to help their reputations, and that led to a search for original manuscript copies, as opposed to the usual arie antiche arrangements of such pieces as “Per la gloria d’adoravi” (Bononcini’s Griselda). Much attention went in the 18 selections of The Royal Trio to presenting Handel’s rivals at their most favorable and characteristic, alongside Handel’s own work from that period. The results are entertaining, in particular Bononcini’s light touch and gift for easily memorable melody. But lacking the theatrical and musical context of a full performance, such numbers as the pair forming the prison scene from Ariosti’s Coriolano can only hint at the full power of the opera. Not that I’m ungrateful for the glimpse, but as “Va tacito” shows, a good amount of the effect comes from understanding the text’s strategic placement in the libretto, and its musical placement between numbers to either side. Lawrence Zazzo’s performances in general have been well received by critics here at Fanfare over more than a decade, including myself. Still, he’s been very active on stage and records for some time, and is currently in his mid-40s. I had my hopes for this album, but also my concerns, as it’s not unusual for even the most astute of singers to show some vocal wear and tear by that time in their careers. Both hopes and concerns, as it turned out, were warranted to a degree in this release. The positives, first. A few low notes to one side, where the voice suddenly shifts into tenor, Zazzo’s alto maintains its tonal evenness throughout its range. His enunciation remains good, and that’s important because one of his strong points has long been his ability to make much of an aria’s or recitative’s expressive content of through heightening consonants and vowels. Zazzo isn’t a singer who gives an impression of emotional inertness. The relatively quick tempo set by Bates for that Ariosti prison scene mentioned earlier hobbles its theatricality, but there’s never any doubt what Coriolano is feeling during it, thanks to Zazzo’s interpretation. This carries across into the slower arias as well, where phrases spaciously, spinning a bel canto line as he varies dynamics. At the same time, the quantity of slow and medium tempo arias perhaps demonstrates an awareness that the extremely fast fireworks pieces aren’t the most successful things on the album. (And even one of the faster arias, “Freme l’onda” from Ariosti’s Il naufragio vicino, just leaves the singer commenting briefly at several points, with only some moderate coloratura towards its conclusion.) A piece such as “Vivi, tiranno” (Handel’s Rodelinda) has some sketchy and tonally insecure fioritura, while “Tigre piagata” (Bononcini’s Muzio Scevola) has some approximate pitching and a loss of breath. He trills well, and can vary both his vibrato and its intensity, but lacks the metal for a hunt-like number such as “Torrente che scende” (Bononcini’s Crispo). Even “Per la gloria d’adoravi,” despite tasteful decorations and some subtle dynamics, ends up too loud at phrase endings, too indelicate to score its points. At its best in “Cosi stanco Pellegrino” (Bononcini’s Vespasiano), “Chiudetevi niei lumi (Handel’s Admeto), and “Tanti affanni” (Handel’s Ottone), this album gives us more than a glimpse of a fine dramatic artist who knows how to shape arias carefully and to maximum effect. I could only wish more of it was on that level. Earlier I criticized David Bates for pushing the pace in Coriolano’s prison scene. Much the same can be said of “Per la gloria d’adoravi,” where it might have had a negative impact on Zazzo’s phrasing. On the other hand, a quicker tempo works to the advantage of “Va tacito,” where sharp accenting of the meter and La Nuova Musica’s precision supplies less an impression of weight than several other performances, and more of treading through danger. The horns are exceptionally good here; and given the quality of the orchestra, their four overtures and sinfonias are welcome in the album. A decidedly mixed reaction, then, to A Royal Trio. It should, if nothing else, create some interest in the music of Handel’s main operatic rivals at The Royal Academy. But I can’t help wishing it had been made with a fresher voiced Zazzo, and perhaps with other artists to provide some tonal variety. Recommended, with reservations. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|