Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

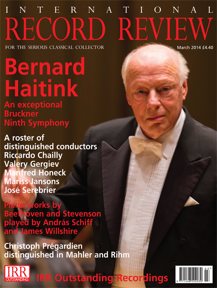

International Record Review - (03//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

BIS

BIS2055

7318599920559 (ID394)

If I am not mistaken, about half of Jakob Lindberg's generous‑length recital (all the works by Daniel Bacheler, Robert Johnson, Cuthbert Hely and Jacques Gaultier) comes from the Lord Herbert of Cherbury Lute Book, a manuscript coIIection of pieces for nine‑ or ten‑course lute in standard Renaissance tuning that was compiled between about 1629 and 1640. By the 1630s, that form of the lute was well and truly being supplanted by the larger 12‑course French lute in the new D minor timing, so the collection was somewhat backwards‑looking. The three lengthy works by Dowland on the disc are from other sources, which Lindberg identifies in his notes, and are probably late works dating from after James I's accession in 1603. The anonymous florid variations on John Come Kiss Me Now. And its associated Prelude come from The Cozens Lute Book, , w'hich was likely compiled before 1603. Thomas Robinson's attractive pieces are from The Schoole of Musicke, which he published in 1603 with an opportunistic dedication to the newly crowned King. The sources of the handful of rather interesting seventeenth‑century Scottish lute pieces are net identified.

Bacheler and Johnson were of the generation after Dowland and, like him, probably began playing smaller lutes. However, their pieces in the programme often extend into the deep ninth and tenth courses. The obscure Hely, whose whole oeuvre save one is found only in the Cherbury Lute Book, is from the next generation again and, while informed by the practices of the 'Golden Age' of the English lute, his quirkily angular and resolutely contrapuntal music lurks in the instrument's sombre bottom and middle ranges and largely avoids the top string.

The three short stile brisé pieces attributed to Gaultier afford us a tiny glimpse of the large body of French music (largely courantes) in English lute collections of the period. As Queen Henrietta Maria's teacher and one of her household musicians from around 1625 to 1640, he was the most influential lutenist in England, even though he seems never to have written anything approaching the profundity of Dowland, Bacheler or Johnson. An outstanding performer but scandalous and violent character (he was once reported as boasting that with his lute 'he could make his way even into the royal bed'), Gaultier fled France for England in 1617 after killing his noble opponent in a duel, apparently by ungentlemanly means. He quickly won the protection of James I's favourite, George Villiers (later Duke of Buckingham), leading to his royal employment.

In his notes for his 1991 disc of pieces from the Cherbury Lute Book, Paul O'Dette quoted a contemporary English description of Gaultier, praising 'the goodness of his hands ‑the most swift, the neatest and most even that ever were'. Though Lindberg does not quite match O'Dette in nimbleness and prefers generally slower tempos, that description is still apt for his playing on this disc. Like O'Dette, he is unfazed by the virtuosic demands of Bacheler's long, elaborately ornamented variations on the famous La jeune fillette (known as La Monica in Italy) and Mounsier’s Almain, two of the most technically demanding works in the lute repertoire. But what really impress are the security of his playing and the maturity of his interpretations of both the serious and more jolly pieces. His sensitive and beautifully paced account of Johnson's long, intensely melancholy Pavan (in which, unlike Nigel North, he does net substitute his own divisions) is especially interesting. Along with Dowland's A Fancy and SirJohn Langton’s Pavan which open and close the programme and Bacheler's La jeune.fillette, it is a high point of the programme.

The instrument Lindberg plays with so sensitive and sure a touch is also of considerable interest. It was made by the Augsburg luthier Sixtus Rauwolf in about 1590 and then enlarged from seven or eight courses to eleven in 1715. It may be the oldest playable lute with its original soundboard, which dendrochronological analysis has determined came from a pine tree that was growing between 1418 and 1560. Sixteenth‑ and seventeenth‑century lutenists believed a lute required many decades for its tone to mature. Recorded close to the microphone, Lindberg's instrument has a rich and luminous tone, albeit less bright than the modern instruments O'Dette and North used. The creaking noises ,while he plays are not signs of structural weakness but come from the gut strings being pressed on the fingerboard.

The instrument gains considerably from playing this disc on a dedicated SACD player: the high resolution sound available by this means is especially suited to such a delicate instrument and gives the recording a striking immediacy. Eyes closed, one has a strong illusion of being in the studio with Lindberg. Those without an SACD player need not despair, however, for the standard stereo CD version included on the disc still sounds wonderfully clear and natural ‑ as one bas come to expect from the ever‑reliable BIS label. Lindberg’s lucid comments about the programme also deserve mention.

A 'must for anyone interested in the lute or the music of the Jacobean era.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews