Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

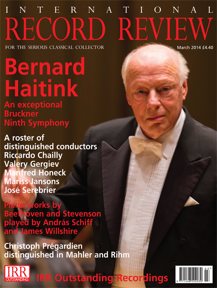

International Record Review - (03//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Aparté

AP061

3149028040326 (ID361)

When I was growing up, the grand French operas created

during the reign of the Sun King, particularly those written by Lully,

seemed pretty much beyond revival. They do not lend themselves well to the

performance of extracts and highlights, with the important exception of

their numerous dance interludes — which formed the basis of the orchestral

suite created by the German Lullistes. There are few arias in the

sense we usually understand the term and such as there are often do not

impress when taken out of their dramatic context. Finally, the grandiosity

of their hero-worshipping prologues (mostly telling us in thinly veiled

allegory what a grand fellow Louis XIV was), the unpleasant character of

Lully and sluggish modern-instrument performances may also have contributed

to their general low esteem. All of that changed with the 1987 Hammonia

Mundi release of Lully’s Atys conducted by William Christie, with the

incomparable Guy de Mey in the title role. That recording followed staged

performances which adopted authentically lavish seventeenth-century costumes

and sets (a highly desirable practice in which Christie seems to have lost

interest). For the first time, modern audiences realized that Lully was, as

Louis had know along, a creator of moving and ravishingly beautiful musical

dramas.

We also learnt that they had to be listened to in their entirety to

appreciate their almost seamless flow of dance, chorus, recitative, arioso

and semi-aria (to borrow not quite apposite terms from Italy) . Since then,

the corpus of period-instrument recordings of complete Lully operas has

grown rapidly.

Phaéton was first performed at the newly completed Palace of Versailles in 1683. Its libretto was written by Philippe Quinault, in close collaboration with Lully. It takes the story of the son of Apollo from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Onto the basic story of a proud young man who recklessly takes his father’s sun chariot for a ride and has to be struck down by Jupiter to protect the earth, Quinault introduces new characters to overlay some typically Baroque romantic complications. Modern audiences may be tempted to see in the arrogant character of Phaéton some subtle criticism of Louis XIV. This is very unlikely to have been either the composer’s or poet’s intention. As the noted Lully scholar Jean Duron points out in his comprehensive booklet essay, contemporary audiences would have identified their king with Jupiter, who has brought in a golden age, not with the rash, power hungry and destructive demi-god. Among other candidates, it is possible that the presumptuous William III of Orange the Phaéton Louis would have to strike down with his thunderbolt.

This new production conducted by Christophe Rousset has many virtues and, alas, some serious deficiencies. (There is an earlier recording by Marc Minkowski, released on Erato in 1994, which I have not heard.) To deal with the shortcomings first: some of the male singers and all of the female singers (except those in the tiniest roles) have unpleasantly rough voices for music of such grace and delicacy. The two female leads, Ingrid Perruche (Clymène) and Isabelle Druet (Théone), both have a strong and persistent vibrato that is at odds with the surrounding instrumental timbre and which makes impossible to tell whether a particular phrase is a trill or a wobble. Lully meant us to sympathize with the tragic Théone and dislike the vengeful Clymène. In this recording, they sound very alike in their deeply unidiomatic singing and neither successfully conveys her character. Sad to say, using singers such as these two is not an aberration: for all his profound love and knowledge of French Baroque idiom, Rousset has shown a strong predilection for these types of female voices (as do Minkowski, Skip Sempé and, these days, Christie).

There is better news with respect to the two main tenors: Emiliano Gonzalez Toro, as Phaéton, and Cyril Auvity in three roles, have just the sort of high-lying, flexible and mellifluous young voices that the opera demands — in the tradition of de Mey, in fact. They are both so good in their often very demanding music that this very success makes their matronly female counterparts sound all the more miscast. Lully’s sumptuous choruses are very well sung by the expert Choeur de Chambre de Namur, whose sopranos include singers such as Zsuzsi Toth, who would have been much better suited to the roles performed by Perruche and Druet.

In the opera’s important and unfailingly lovely orchestral writing, the orchestra of Les Talens Lyriques, playing in the Fmench Baroque configuration of five string parts, is startlingly good: lush, rich and highly disciplined. The gorgeous orchestral chaconne at the end of Act 2 together with the singing of Auvity and Gonzalez Toro, the highlight of the set. The opera was recorded live, but stage and audience noises are barely discernible. The set is handsomely packaged in a hardback format with full texts and translations. One word of caution, however: if you accidently hold the box upside down, the discs can easily slip out (and, in my case, roll under the car seat).

Despite its casting misjudgements, this recording should confirm Lully’s reputation as an opera composer of the first rank.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews