Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

| Recommended |

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

Reviewer: Bertil

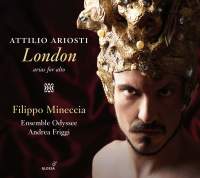

van Boer The various pieces, including cantatas, for the viola d’amore are his main forte, but the many operas he wrote are equally impressive. As the fine booklet notes mention, he was extremely persnickety about his orchestration (as opposed to Handel and others who were more lax), often indicating which instruments he wanted for his continuo grouping at each aria. Add to this a penchant for writing interesting and progressive introductions, and one has the idea that Ariosti was worth every bit of his reputation as a composer in total. This disc does give a good cross section of works drawn from a good span of his career, from his earlier works in Vienna to the last (and certainly most famous) in London. There are, of course, some considerable stylistic differences that are notable. For example, the aria “Bella mia, lascia ch’io vada” from the 1704 Scipione is quite old fashioned, with a simple continuo introduction featuring the theorbo and a meandering vocal line that seems right out of Alessandro Scarlatti. In a similar vein, the sinfonia of the 1705 opera La profezia is a cross between Corelli and Scarlatti, lacking the more definitive rhythms of the later French style London overtures, such as the pompous and noble work that begins Coriolano. Ariosti uses a variety of compositional techniques to highlight interest. In “Aure care” from Tito Manolo, the gentle breezes are depicted as a moderate paced Siciliano. The aria “Premerà scoglio” from the 1724 Vespasiano is based on a rather strict ground, which proceeds chaconne-like as the voice soars in contrary motion upwards by thirds in the main theme before winding all about the steady line in twisting roulades. In “Rinasce amor” from Aquillio Consolo from the same year, the opening unisons are stark contrasts to the rising suspensions. Ariosti does not shy away from coloratura, but he is often less likely to make it the focus of the aria, but rather allow it to develop out of the often lyrical main themes, such as in the final aria of the disc, “Io spero” from Coriolano, in which the recorders warble nicely as if in an opening dream, only to have the faster section break into some twisting and turning roulades vocally as the tempo increases.

These are

all works intended for a castrato, but countertenor Filippo Mineccia does a

terrific job. His voice is powerful and decisive, and as far as I can hear

he doesn’t miss a note. His sense of lyricism is acute, and he knows how to

heighten the emotion of an aria by entering smoothly and unobtrusively at

Ariosti’s often unexpected vocal entrances. The ensemble playing by Odyssee

is well integrated and well phrased, with good tempos that are flexible to

accommodate the textual nuances of the vocal part. They use a larger

ensemble than one-on-a-part, which gives this work depth, and also

corresponds more closely to Ariosti’s London orchestra, the exception being

the oratorio La madre de’Maccabei, where the composer actually pretty much

insists upon a lesser textural scoring in his own instrumentation. All in

all, this gives an excellent sampling of the operatic treasures by one of

Handel’s colleagues. Of course, it is all about the voice and subsequent

characterization done by Mineccia, but there is enough of a glimpse here to

wish for someone to record a complete Ariosti opera.

Recommended.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|