Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Simon

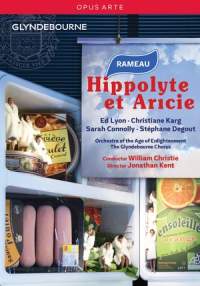

Heighes Today we use 'Baroque' as a convenient label for the music of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, though without much thought to the word's original meaning. 500 years ago extravagant jewellery or complex decoration might have been considered 'baroque', 'but no one actually applied the term to music until 1733 when a reviewer of Jean‑Philippe Rameau's first opera Hippolyte et Aricie complained that it lacked clear melody, continually changed key and ran the gammut of every conceivable compositional device. All this disconcerting complexity was, in a word ‑ 'baroque'.

It was all a bit toomuch for the original cast members, several of whom were either unable or unwillng to master the music's difficulties. This, along with criticisms of the opera's structure, forced Rameau to make cuts and revisions which undermined the opera's dramatic power, and from which it never fully recovered. First revived in 1903, Hippolyte has now finally claimed its rightful place amongst Rameau's finest operas, and the present performance returns to his original and most theatrically convincing version of the work from 1733.

A decade ago I concluded my review of Rameau's Les Boréades from William Christie and Les Arts Florissants (July/August 2004) with Christie's confident prediction that Rameau's operas would 'become much more important in the next few years in the new lyric repertory in Europe and the United States'. And so it has come to pass. Encouraged by the 250th anniversary of Rameau's death in 2014, and the 300th anniversary of the premiere of Hippolyte et Aricie, Glyndebourne opened its expensive doors to him for the first time in 2013 with a performance of Hippolyte conducted by Christie, and given a modern twist by director Jonathan Kent. I hugely enjoyed attending the first performance of this new production and have been thoroughly looking forward to its release on DVD.

The basic plot is fairly straightforward. The Prologue pits the chaste Diana against the love‑obsessed Cupid, and the god Jupiter decrees that for one day a year Cupid will be given free reign. Diana, however, swears to protect the innocent mortals Hippolytus and Aricia. On the dark side are the tragic King and Queen of Athens ‑ Theseus and Phaedra. Phaedra harbours incestuous love for her stepson Hippolytus, and Theseus mistakenly accuses him of raping his stepmother. Both are morally disgraced: Phaedra commits suicide and Theseus (having ordered the death of Hippolytus) discovers that his son has been saved by Diana, but he will never be allowed to sew him again. Ultirmately, Diana reunites the much‑misused Hippolytus and Aricia, and Cupid is vanquished.

For Kent the opera is, at heart, a contest between the rigour of Diana ‑ Goddess of chastity, hunting and fidelity within marriage ‑ and the anarchie, unrestrained passions aroused by Cupid. Kent sees both elements of tragedy and genuine French wit in the unfolding narrative. We get plenty of both in his production, the latter especially well represented in Paul Brown's playful scenic and costume designs, but well balanced by the sheer magnificence of display ‑ les merveilles -fundamental to Rameau's age and vividly reimagined for ours. Though panned in some dull‑minded newspaper reviews back in 2013, Brown's use of chill interiors for several scenes (famously a refrigerator in the Prologue and a mortuary in Act 5) actually work wonderfully well, underpinning and linking the slim narrative thread of repressed love ‑ where the heat of passion is literally frozen into submission.

Each act has its own distinct flavour, but my favourite is the use of the back of the refrigerator as a representation of Hell in Act 2. It's a terrifying place ‑ where most of us would never dare to look - and here it comes complete with dancers dressed as insects and the three Fates masquerading as a trio of evil spiders. Towards the end of the tense third act the sudden appearance of a chorus of camp sailors imported from Showboat (and illuminated with pink neon lights) did rather startle the Glyndebourne audience. But the purpose of Rameau's original chorus is to interrupt Theseus's row with Phaedra ‑ who has been (misleadingly) found in Hippolytus's embrace. Thus Theseus and Phaedra must tough it out in front of the raucous 'welcome home' offered by King Theseus's subjects. We feel the discomfort of the royal couple, and laugh at the dramatic convention which demands that we have to wait for the outcome of this horrendous misunderstanding ‑ which will shape the rest of the drama.

The singing throughout is very persuasive. Sopranos Katherine Watson (Diana) and Ana Quintans (Cupid) inhabit their respective characters wonderfully. Watson deserves special mention for singing much of her role while suspended in mid‑air, and I liked the way that she deliberately hardens her tone and slices through the declamation with a cold edge when she's being imperious, but warms and softens her timbre when praised by her minions and working hard to protect the young lovers. In Christiane Karg's hands Aricia is an innocent. Her simple tone and marked avoidance of real sensual interaction with Hippolytus keep her pure and slightly apart from the darker side of the drama. Whereas Ed Lyon ‑ tall, handsome and throatily appealing ‑ brings just the right degree of hotness to the role to make Phaedra's infatuation with him convincing (though, for me, he's not a patch on the French high tenors Christie usually works with, with their purer, more concentrated tone and real understanding of the suppleness of French declamation and expressive use of cadential appoggiaturas). Like Karg, Lyon too never really allows himself to make vocal love to his sweetheart. There's a degree of emotional restraint about their relationship ‑ clearly unconsummated ‑ which seems designed to throw the real protagonists of the drama into relief.

Rather like Mozart's Figaro, it's not the youngsters (Figaro and Susanna; Hippolytus and Aricia) who are the underlying focus, it's the relationship between the older couple (Count and Countess; Theseus and Phaedra) which really turns the cogs of the drama. This is where the finest moments are. Theseus, sung by Stéphane Degout, is a richly resonant and rounded character. Degout has a natural gravitas, and though he tends towards dynamic rather than tonal shading, his instinctive feel for the language and drama make for a compelling portrayal. If his baritone occasionally seems a little unbending it's only in comparison with the suprernely nuanced singing of Sarah Connolly ‑ the spellbinding Phaedra. From her first entry in Act 1, Connolly is the dominant presence onstage, communicating as much with her body and face as she does with her singing. At the start of Act 3 she lets the pain and passion of her illicit love flood her voice ‑ rich, quivering and varying from phrase te phrase, and yet drawn together into compelling paragraphs of grief. One of the high points of the performance is the close of Act 4, where Phaedra hears of Hippolytus's death and realizes that it's ultimately lier doing. The ernotion wells; up from deep within Connolly, and lier final accompanied recitatives, delivered with such concentrated tone and so powerfully underpinned by the orchestra, express a perfectly calibrated mixture of guilt and atonement. The curtains corne down behind lier. The audience draws breath and very slowly, in total silence, she descends the steps into the dark orchestral pit ‑ embracing death. So powerful; so moving.

The Glyndebourne Chorus is superbly confident onstage and never afraid to raise the roof, especially in the great hunting scene in Act 4, where it is joined by the braying horn of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. The strings play with terrific tonal richness when accompanying the long stretches of soulful declamatory singing, and the flutes have been expertly recorded, remaining audible in even the softest passages. There's a whole separate review to write about the ballet ‑ but suffice to say that the eight dancers are beautifully integrated with the chorus and their steps emerge effortlessly from out of the crowd. It's all modem choreography, and very closely tied to the drama.

Camera‑work and sound (especially on the Blu‑ray version) are crisp and

vivid, with the orchestra perfectly balanced to the fine house acoustic and

satisfyingly bass‑rich (I counted three double basses on the bottom end of

the OAE). We also get a short bonus documentary explaining the thinking

behind the production, with revealing comments from the director, designer,

choreographer and cast members. For those relatively new to French Baroque

opera, Christie has a parting word of encouragement: 'It's music that

requires a bit of getting in to. But once you've bought into it, you won't

forget it and it will stay with you for a long time.' His predictions, like

his direction, are not only reliable but inspiring. This is a triumph: a

hugely enjoyable production, with extremes of humour and pathos, and an

emotional shift of gravity which renders this less Hippolyte et Aricie

than Thésée et Phèdre. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|