Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

*

International Record Review - (02//2014)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

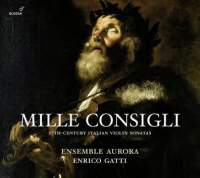

Glossa

GLO921208

Code-barres / Barcode : 8424562212084 (ID373)

The title of this disc, ‘Mille Consigli’ (‘a thousand inspirations’ ) , is not the name of one of the sonatas in the programme, as I imagined on first seeing it in the new release listing (shades of Antonio Bertali’s Tausend-Gulden sonata perhaps), but a phrase used in lengthy passage quoted in the booklet, taken from Le Instabilità dell’ingegno, a Boccaccio inspired book by the seventeenth-century Genoese nobleman, Jesuit priest and religious and satirical writer, the Marchese Anton Giulio Brignole Sale. Using high-flown poetic language, it describes in detail the early-morning vocal display of a nightingale in a villa garden. Neither Sale nor his book has any direct connection with the music on this disc, but the quotation reminds us of the extraordinary fecundity of invention and improvisatory virtuosity of the instrumental music of early to mid-seventeenth-century Italy, which, like the song of Sale’s nightingale, ‘varies in each moment a thousand inspirations’.

Enrico Gatti and his colleagues have selected an interesting and varied collection of Italian violin sonatas, a ciaccona and two highly ornamented instrumental versions of a motet and madrigal by Palestrina from the first half of the seventeenth century, plus solo apiece for the dulcian player Elena Bianchi, theorbo player Gabriele Palomba and organist Fabio Ciofini.

An important theme of this disc is the development of the basso continuo in early seventeenth-century Italy and how it would have been realized by the musicians of that period. A very important sub-theme is the type of organ that is appropriate for Italian instrumental music much of which was intended to be performed mainly in church. The Italian musicologist Daniele Torelli devotes a considerable part of his booklet essay to this — so much, in fact, that more than halfway through he feels compelled to remind us of the pre-eminence of the solo parts — before turning back to the organ.

This is an instrument made by the Roman organ builder Luca Neri in 1647 and installed in the gallery above the main entrance of the collegiate church of San Nicolò in Collescipoli near Terni in Umbria. A detailed description of its construction and disposition is provided in the booklet. It is unlike the powerful behemoths for which the composers of the North German Baroque wrote. While it is capable of ringing out brilliantly, as it does in Ciofi’s expertly played solo, Michelangelo Rossi’s Toccata settima (published in 1640), it is quite soft-voiced in the historically accurate registrations employed by Ciofi when playing continuo and is thus wonderfully suited to accompanying both the violin and dulcian ( predecessor of the bassoon). Two works, the longest in the recital, demonstrate especially the aptness of the organ in this repertory: Bertali’s toe-tapping Chiacona a violino solo and the astonishingly demanding Sonata seconda for solo dulcian by Giovanni Antonio Bertoli. So too does Marco Uccellini’s Sonata, Op. 7 No. 3 with its very active continuo part. In all three works, the organ’s firm, rounded ‘singing’ tone is an ideal complement to the more astringent sounds of the solo instruments. Bianchi also displays in Bertoli’s sonata extraordinary nimbleness and breath control allied with superb musicianship, making this a perhaps unlikely high point of the whole recital.

The acoustic of San Nicolò’s Church is an added bonus, for instead of the customary heavy reverberance of a church building that could easily swamp the instruments its simultaneously spacious and intimate acoustic, helped by superlative sound engineering, brings out perfectly the individual qualities of each instrument.

Which brings us to the performances. The Italian seventeenth century seems to be where Gatti’s heart as a musician lies. For him, it appears the essence of its music is not to be found in the exaggerated effects favoured by other specialists in this period, such as sudden wild shifts of tempo and dynamics or abrupt extreme changes of tone. Rather, his playing is marked by an overall smooth, sweet sound that is yet stiffened with genuine authentic tonal fibre and modulated by ever-varying delicate colorations and almost rhapsodic phrasing. This is best exemplified in Uccellini’s melodious Sonata, Op. 7 No. 3 for solo violin and continuo, perhaps the most sophisticated work in the whole programme. To ears used to the robust and highly mannered style of other period violinists in this repertory, Gatti’s relaxed and almost mild approach initially can seem a little staid; but, as with eyes adjusting to a darkened room, the subtle lines and glowing colours of his playing quickly emerge. What is revealed is an almost vocal expression of the music. Interestingly, Bianchi’s dulcian matches Gatti in this respect, despite the combination of her instrument’s demanding technique and its very different voice from the violin’s.

This is one of the best recordings of Italian

early-Baroque instrumental music I have heard.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews