Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

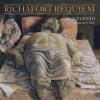

Jean Richafort, (c.1480-c.1547),

Fanfare Magazine: 36:3 (01-02/2012)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

Hyperion

CDA67959

0034571179599 (ID240)

"Requiem" et oeuvres sacrées par / and sacred music by Després, Gombert,

Vinders,

Ensemble Cinquecento

Josquin’s death is the theme of this release, with three musical laments that were published in 1545 by Tielman Susato. Two of them set Gerard Avidius’s poem, Musae Jovis, a conventional humanist deploration that involves the Muses and Roman gods—though Appenzeller omits the second half of the work, ending on a mournful note of loss, while Gombert continues with the rejoicing that follows upon Josquin’s welcome onto Mount Olympus, where he sings ever so sweetly.

But the main object of interest here is the Requiem Mass dedicated to him by Richafort. This is only the third recording of the work that I’m aware of. The first, featuring Christopher Wolverton and the Vox Early Music Ensemble (available from voxannarbor.org), I’ve yet to hear. The second, with Paul van Nevel and the Huelgas Ensemble (Harmonia Mundi 901730), was reviewed by J. F. Weber in Fanfare 26:2. Nevel took strong exception in his liner notes to comments in Allan W Atlas’s Renaissance Music referring to the post-Josquin generation in a slightly disparaging fashion; and I might add that Richafort and Manchicourt aren’t “solid if unexciting” by my way of thinking either. But then, such observations might be predicated in part upon viewing Richafort as post-Josquin, when in fact his lack of the expressivity found in many of his contemporaries makes him seem almost a pre-Josquin throwback. But do we regard Ockeghem as “solid if unexciting?”

Stephen Rice, in his liner notes to the new release, correctly points out the various ways Richafort invokes Josquin in this Mass. There’s the cantus firmus running under the Requiem chant that utilizes the Circumdederunt me Josquin set in a polytextural motet. As in that motet, Richafort’s Mass treats the plainsong canonically, with the accompanying voice entering at a fifth above, three breves’ distance. There’s also a quote worked in from a chanson by Josquin that parodies the language and chest-heaving theatrics of courtly love, Faulte d’argent (which again, is on this album). Nor is it easy to ignore the ingenious contrapuntal treatment throughout the work, definitely reminiscent of the Requiem’s subject.

Both Cinquecento and Nevel focus on individual lines, rather than striving for a homogenous sound. One major difference is that the Huelgas Ensemble is a flexible group of a dozen singers or more, while Cinquecento has six (and adds a seventh for the seven-part Vinders work). Some might remark that doubling the voices, as Nevel has done, is out of step with modern musicological research, but in fact there was no standard for performance numbers at the time; and when the money to afford a larger musical establishment was available, it was sometimes invested in multiple singers per part. The slightly distant, moderately over-reverberant sound in the Nevel emphasizes this size, however, and it has to be admitted that the brighter, closer engineering Hyperion supplies makes it easier to follow Richafort’s six parts. Another difference between the two versions is that Cinquecento’s tempos are generally faster than Nevel’s throughout, noticeably so in the Kyrie, where they sound almost nervous by comparison.

Nevel fills out the rest of his album with motets and chansons by Richafort, not otherwise available. Everything else on this release has been previously recorded, however, in some instances, repeatedly. (Nymphes des bois/Requiem shows up on ArkivMusic.com as having 19 versions currently in print, though a few of these, like two by the Orlando Consort, are identical.) So if you’re a collector who already has much of this content, you probably should consider Nevel/Huelgas, all other matters being equal. I find the performances relatively equal in merit, with Cinquecento more transparent in texture, but also too fast in its choice of tempos on occasion.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews