Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

Fanfare Magazine: 36:6 (07-08/2013)

Pour

s'abonner / Subscription information

Les abonnés à Fanfare Magazine ont accès aux archives du

magazine sur internet.

Subscribers to Fanfare Magazine have access to the archives of the magazine

on the net.

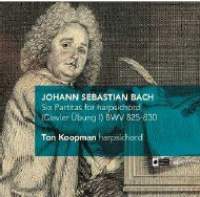

Challenge Classics

CC72574

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

As

the excellent program notes by scholar Christoph Wolff point out, Johann

Sebastian Bach was expected to establish himself as a keyboard expert for

his new position in Leipzig. There were, of course, numerous ways of going

about this, but he chose to issue sets of suites, a form that had already

been popularized by his predecessor, Johann Kuhnau, some two decades

earlier, regarding them mainly as pedagogical works since he was not really

in a position to begin a secondary career as a keyboard virtuoso. In the

fall of 1726 he announced their publication in the town newspaper,

eventually completing the set of six in 1730. Wolff makes a persuasive case

that the full set ought to have contained seven partitas, but Bach preferred

six, mixing up the major and minor modes and avoiding the flat seventh (B♭)

in order to achieve a complete set.

It should be remembered that these six suites are primarily meant as keyboard exercises, both for performers and potential composers who needed to learn how to write the “Praeludien, Allemanden, Couranten, Sarabanden, Giguen, Menuetten, und andere Galanterien” that the genre required. As such, they were invaluable as educational tools, regardless of whether or not one studied them with a teacher. It is also somewhat debatable if they were actually intended to be performed, as were George Fredrick Handel’s 1720 Great Suites. Of the many exercise books that musicians have struggled with over the ages on all instruments, from Rode to Czerny, live performance would be a soporific experience, though of course a recording could be used as a comparative model (which is probably why such things are done at all). For these works, however, the variety supersedes such questions. What never ceases to amaze me is the variety of ways that Bach interprets each movement of each suite. From the gentle imitation of the opening to the first partita to the powerful full-voiced dotted rhythms and complex melodic line over a meandering bass of the second section of the second partita to the fantasy-filled sweeps of the sixth (titled Toccata), there is depth and variety. This of course extends to the other movements as well. Personally, I often like to judge the performances by the various “gallantries” that Bach inserts, such as the Rondeaux and Capriccio of the second partita, the Burlesca and scherzo of the third, the Gavotta of the sixth, and the Passepied of the fifth.

Of course we have a number of excellent recordings of this set, including that by Christophe Rousset on L’Oiseau Lyre. The venerable Ton Koopman now adds his rendition to the mix, and I am pleased to say that it measures up. His tempos tend towards the more lively, and his decisive articulation and phrasing bring out some of the more subtle details of the suites, such as his pointed version of the Rondeaux from the second partita. This is not mere grinding out of repetitive sequencing, but a nicely detailed set of performances, all of which serve to highlight the multiple tasks for which these partitas were intended by their creator. If you do not have a harpsichord version in your collection already, this is one you might well include.

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD

Click either button for many other reviews