Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|

|

|

|

Polyhymnia, he points out to the implacable Boreas ‘you can be feared, but can you be loved?’ In the nick of time, Apollo descends to reveal that Abaris is his own son by a Boread nymph – which means that the hero is eligible to marry into the monarchy of Bactria. From a certain point of view, Rameau’s final tragédie en musique is an allegory for goodness and light banishing the darkness of evil authoritarianism.

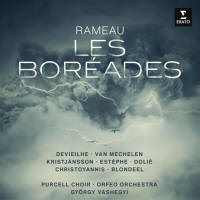

The belated world premiere of Les Boréades was Gardiner’s concert performance at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1975; seven years later he conducted the work’s first-ever staged production at Aixen-Provence (captured on the English Baroque Soloists’s seminal recording). Liberated recently from decades of complicated legal wranglings, the score was recorded afresh by Collegium 1704 and Václav Luks. Now, Sylvie Bouissou’s hotoff-the-press scholarly edition (Bärenreiter, 2024) underpins this collaboration between the Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles and György Vashegyi.

Valuable aspects of historical performance practice are applied fastidiously by Orfeo Orchestra: the harpsichordist never plays in dances, a double bass is used in the continuo, and oboes are chosen over clarinets (apparently Rameau changed his mind against using the latter). There are more than 40 players; the orchestra’s large scale and balance boasts quadrupled double basses, flutes (two also on piccolos), oboes and bassoons. There are lively interchanges between braying horns and fruity oboes in the overture, pastoral dances have contoured delicacy, an entrée for the followers of Borilée and Calisis conveys bassoon-laden pomposity, and the relaxed entrée of Polyhymnia has gorgeously unfurling echoes between flutes and bassoons.

Reinoud Van Mechelen and Sabine Devieilhe deliver ample sophistication and dynamism in key moments such as Abaris’s anguished yet refined plaint (‘Charmes trop dangereux, malheureuse tendresse’) and Alphise’s juxtaposition of troubled anxiety and serene hopes (‘Songe affreux, image cruelle’); their mutual realisation of politically imprudent love compounds intense passion and soft tenderness, and their ensuing trials mingle together pathos and resolve. Gwendoline Blondeel’s nuanced agility and sweetness makes mincemeat of Sémire’s fluctuating anticipation of gathering storms (‘Un horizon serein’), and the soprano multitasks as Cupid, the reassuring Polyhymnia and a nymph extolling freedom from amorous snares.

The initial suavity of Philippe Estèphe (Borilée) and Benedikt Kristjánsson (Calisis) erodes into bullying fury upon Alphise abdicating and presenting Cupid’s arrow to Arbaris – their tempestuous duet has crashing sound effects of thunder and howling winds generated by good oldfashioned Baroque technology (‘Vents furieux, tyrans des airs’). Thomas Dolié makes a bold impact as their vengeful father Borée, commanding the devastating winds (a male chorus) in an ombra scene of extraordinarily intricate yet darkly whispered music. Tassis Christoyannis doubles up as the high priest Adamas (Arbaris’s adoptive father) and Apollo.

The Purcell Choir contribute polished textural precision and lucid expression of words to several crowd scenes, such as ardent exchanges with Kristjánsson’s rapid high-wire coloratura (‘Jouissons de nos beaux ans’), the Bactrians veering between despair and fear (when Act 3 segues stormily into Act 4), and the dazzled amazement of the gloom-loving Boreads to the radiant sun god Apollo. In all respects, Vashegyi’s marvellous take on Les Boréades confirms how far Rameau’s art and ideas developed across his 30-year operatic career. |

|