Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

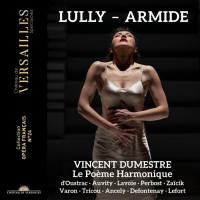

Like Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques, Vincent Dumestre and Le Poème Harmonique are working their way through the operas of Lully. Rousset’s recording of Atys appeared recently (4/24); here, on the same label, is Dumestre’s Armide, strong competition for the Rousset version issued some years ago.

Armide was Lully’s last completed tragédie en musique and his last collaboration with the librettist Philippe Quinault. It was premiered at the Opéra on February 15, 1686; 13 months later the composer was dead, having in the interim produced the pastorale-heroïque Acis et Galatée and embarked on the tragedy Achille et Polyxène (which was to be completed by Pascale Collasse). As with the two previous operas, Amadis and Roland, the subject had been chosen by Louis XIV; but Louis never saw Armide, because he was undergoing a painful operation. It was not staged at Versailles during the king’s lifetime.

If the gestation of the opera was difficult – among other things, Lully was out of favour on account of a scandal in his private life – its birth and progress were triumphant. Armide was greatly admired, and it was revived several times up to the 1760s. The subject was taken from Tasso’s epic poem Gerusalemme liberata, set at the time of the First Crusade. The warrior priestess Armide, fresh from a victory over the crusaders, regrets that she has not defeated the paladin Renaud. When she falls in love with him she uses her magical powers to make him equally smitten. But Renaud comes to his senses, reluctantly puts duty before pleasure, and leaves with his fellow knights.

Lully is here at the height of his powers. Armide is not really a love story, as Renaud has been bewitched, but there is a love duet of melting tenderness. The divertissements include one of Lully’s sleep scenes and a splendid choral and orchestral passacaille. Act 4 is, literally, a diversion: an irrelevant scene where Renaud’s companions Ubalde and the Danish Knight are temporarily deceived into thinking that the demons before them are their lovers from home. I say ‘irrelevant’, but you could argue that the act provides a necessary dramatic breathing space after the scene where Armide summons La Haine (Hatred) and before the tragic conclusion.

Obvious as it may seem, it’s worth stressing that the opera belongs to Armide. She is not a wicked witch but a fallible, sensitive woman whom Quinault shows from every angle. The part is a perfect vehicle for Stéphanie d’Oustrac, who played it years ago at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Robert Carsen’s production fortunately preserved on DVD. There are two great monologues. ‘Enfin, il est en ma puissance’, attacked nearly 70 years later by Rousseau and defended by Rameau, comes at the end of Act 2, when Armide is about to stab the sleeping Renaud but is overcome by love. At the end, in ‘Le perfide Renaud me fuit’, she rages, then (we may presume) weeps, and finally destroys the palace. The first is accompanied by the continuo instruments, the second brings in the orchestra. In both, d’Oustrac weighs every word, her timing superbly judged. Her despair at ‘Que disje? Où suis-je?’ is palpable. Summoning Hatred, then rejecting her (definitely female, albeit written for a baritone), she is as imperious there as she is tender later.

Renaud himself is sung by Cyril Auvity, promoted from two small roles on the Rousset recording. He has plenty of experience in this repertoire: at times on earlier recordings there has been something uningratiating about his tone – I wouldn’t go so far as to describe it as bleating – but at his best, as in the love duet, he is a match for d’Oustrac. Tomislav Lavoie and Timothée Varon sing powerfully as Hidraot and La Haine respectively. The smaller parts are well taken, with some mellifluous singing in thirds from Eva Zaïcik and Marie Perbost in the allegorical Prologue. Choir and orchestra sing and play lustily, and the continuo group of three theorbos and harpsichord is splendidly sonorous.

Vincent Dumestre, another old hand, conducts stylishly and sensitively, though right from the start he rather overdoes the swelling on sustained chords in the strings. In the Second Air in Act 2 he replaces the strings with what sounds like a pair of viols: on what authority I don’t know, but the effect is certainly beautiful. The libretto in the booklet is a shambles: words printed that aren’t sung, words not printed that are sung; while Act 4 scene 2 is in such disarray that you’d be better off following the text in the Rousset set. And I don’t suppose Stéphanie d’Oustrac would care to be described (on the back of the cardboard container, in English) as ‘immense’.

I wouldn’t recommend this above Rousset’s recording, with its excellent cast led by Marie-Adeline Henry and Antonio Figueroa, but it’s certainly worth hearing.

And, as with Atys, the DVD recording by William Christie and Les Arts Florissants with Paul Agnew and, of course, Stéphanie d’Oustrac, is a must-have. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|||||||