Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|

|

|

|

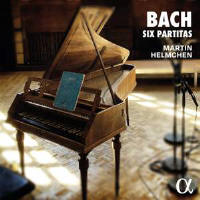

It is still relatively rare these days for established mainstream pianists to fall for an old instrument hook, line and sinker – as distinct from those inspired by the possibilities of ‘period’ articulation, gesture and pedalling (or none) transferred to the modern piano. Martin Helmchen is the embodiment of the most inquisitive of his kind, passionately immersing himself in one of the most enduring of all keyboard collections on an original Späth & Schmahl tangent piano from 1790. The tangent piano, only briefly in vogue, was designed alongside the emergence of the fortepiano to bring dynamic range and expression through touch on the keys, unachievable on the harpsichord. If it was soon surpassed by the fortepiano’s more even profile across its range, there is – on the evidence of this compelling recording of Bach’s Partitas – a beguiling twilight zone where it bridges the world of the harpsichord (also redolent at times of the intimacy of the clavichord) and the emerging piano.

The performances are by no means driven as an exercise in museum curation. Helmchen is drawn to the hybrid capabilities of his instrument, which stimulate fresh insights into how Bach’s Partitas can be played and experienced. From the opening of the First Partita the ear must make a few adjustments: away from the glistening resonance of, say, a Ruckers harpsichord or the smoothly regulated curvature of a modern Steinway, towards an intimacy and poetic gentleness which come to the fore amid a compact homespun affability. This is where Helmchen’s artistic vision matches the technical whims of the instrument. The lucidity of the Corrente’s counterpoint is revelatory and more joyous than I can ever recall (the same can be said for the deliciously swung syncopations in the Corrente of the Sixth Partita), and the Sarabande unfolds utterly graciously with a singing right hand that had me following the line like a dog on a scent.

It is the connectiveness of the interweaving parts and the harmonic textures that makes for such an unusually communicative experience. Given the richness of detail at every turn in the Partitas, it is a slight shame that Helmchen feels that he must scale it up further – literally with a surfeit of studiously planned runs on the repeats. This is mildly tiresome, but jars only really in the Allemande and Menuet I of the First Partita. Elsewhere, the music-making is replete with character, virtuosity, charm and colour. Both the Second and Fourth Partitas, especially, bring out the grandeur, sweep and decorative élan of the music. The fugue in the former’s Sinfonia is a concentrated and cultivated affair, followed by a finely projected account of the nobly imploring Allemande, a wonderfully contrasted and spiky Courante and world-weary Sarabande. The Fourth has a range of fulsome conceits recalling Ketil Haugsand’s distinguished reading (Simax, 1/95).

Underpinning admiration for this recording is Helmchen’s imaginative toying with the paradox of using a historical instrument that is too late to be historical for Bach’s time, and yet which uncovers a deeply compelling language of polyphonic interaction and beauty. Thanks to this historical inveracity, you hear puckish quirks in the opening of the Fifth Partita, a deeply affecting eloquence in its Allemande (where all the inner dialogues seem to sing in close consort), and we are offered overall a rich store of perceptions into the hidden wonders of this unendingly fascinating set of suites. A wonderful new Bachian vista exposed! |

|