Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

The Homecoming of Ulysses, like its successor The Coronation of Poppaea, is a problem opera. It was first performed in 1640 in Venice, probably at the Teatro SS Giovanni e Paolo. The manuscript score, in three acts, is, mysteriously, in Vienna; various manuscript copies of the libretto cast the opera in five acts, and there are other discrepancies. The pacing of the drama is flawed. The disguised Ulysses, returning to Ithaca after a 20-year absence, proves his identity to his wife Penelope; but it takes the whole of the last act for her to be convinced. And yet, in the theatre, both story and music hold your attention, and you rejoice when the couple blend at last in a rapturous duet.

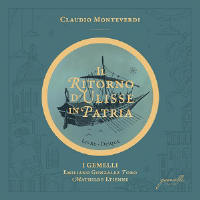

I Gemelli sounds – perhaps deliberately – like the name of one of the literary academies of the time. The founders – not twins but husband and wife – are Emiliano Gonzalez Toro and Mathilde Etienne, who not only sing but are responsible for the performance and the musicological preparation. The music is complete: in fact super-complete, as an unnamed member of the ensemble has filled in the gaps where no music survives – and in one case was possibly never written. This is Act 3 scene 2, where Mercury consigns the shades of the slaughtered Suitors to hell. No reference is made to the source here, which turns out to be a Sinfonia from Il ballo dell’ingrate, published in Monteverdi’s Eighth Book of Madrigals in 1638 but composed as far back as 1608. The words of the missing final chorus of Ithacans have not been set, so the opera ends with that rapturous duet.

The opera theatres in 17th-century Venice were commercial operations. The attractions were the singers and the sets and costumes. There would have been no room in the budget for a lavish instrumental section; what is known about the circumstances at the time (not much, admittedly) suggests that only a handful of string and continuo players were employed. On the other hand, the coronation scene in Poppaea cries out for a pair of cornetts; and, to be fair, the Sinfonia where Ulysses slays the Suitors requires ‘all the instruments’ to play. As is the case with other recordings, such as John Eliot Gardiner’s (SDG, 1/19), I Gemelli bulk out the texture with additional instruments: recorders, cornetts, sackbuts, viols, percussion and a continuo group including triple harp, archlute, theorbo, Baroque guitar and organ.

The sinfonias and ritornellos do sound splendid. Having the instruments accompany the singers in places, with quasi-improvised decoration, is more questionable. But it is mostly done in moderation, and the focus remains firmly on the vocal line. Gonzalez takes the titlerole, and he is magnificent. Like the other characters, indeed, he sings the recitative as a form of heightened speech, blossoming into arioso in the most natural way imaginable; his rant against the Phaeacians who have abandoned him on the shore is powerfully articulated. He even manages to put on a convincingly quavery old man’s voice when required. Zachary Wilder, promoted from Eurimaco on the Gardiner recording, is a perfect match as his son Telemaco. Mathilde Etienne and Álvaro Zambrano find a suitable erotic charge to the duet that makes a sudden contrast to Penelope’s opening soliloquy.

Emoke Baráth copes fluently with Minerva’s roulades. Towards the end Ericlea, Ulysses’ old nurse, holds the stage as she asks herself whether to confirm the hero’s identity to his wife. The scene is held together by a threefold refrain; Alix Le Saux’s tremulous anxiety seems just right for Ericlea’s dilemma. Philippe Talbot makes a vivid Eumete, the loyal shepherd; while Fulvio Bettini almost makes you feel sorry for the glutton Iro in Monteverdi’s parody of a lament as he contemplates his future after the death of the Suitors.

Unusually, the opera proper – after the Prologue – opens with a real lament. Penelope has been waiting for Ulysses to return from Troy, loyally resisting the attentions of the Suitors. Rihab Chaieb brings a moving intensity to the rising chromatic phrase ‘you alone, of your homecoming …’ before dropping despairingly to ‘… have lost sight’. When at last she accepts that the stranger really is her husband, the sense of release is palpable.

Emiliano Gonzalez Toro is responsible for the musical direction. Whether or not this means conducting, there is a precision to the ensemble that speaks of much rehearsal; at the same time, there is a sense of the continuo players responding to the flexible declamation of the singers. Palazzetto Bru Zane style, but bigger (18cm ¨ 24cm), the book enclosing the CDs contains a host of articles, all seemingly by Mathilde Etienne.

|

|