Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

Analyste: Bertil van Boer

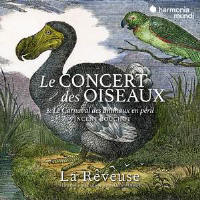

From the title one would immediately think that this disc contained a concert strictly for the birds, and you would be right (though not in the colloquial sense). Composers have always had a fascination with the music of bird calls. One only needs mention, for instance, Vivaldi’s goldfinch flute concerto or the fluttering calls that one finds in “Spring” of The Seasons, or Mozart’s final movement of his G-Major Piano Concerto, or even Beethoven’s second movement of the Sixth Symphony. We will also gloss over Oliver Messiaen’s obsession with ornithology, but suffice it to say that the music of these creatures in nature has provided inspiration and even imitation throughout history. This disc is in two parts: The first is a program of various single pieces by mainly Baroque composers (but also two 19th- and 20th-century ones) dedicated to various birds, ranging from character pieces in keyboard suites to the famed Carnival of the Animals by Camile Saint-Saëns; the second part is a new work by Vincent Bouchot (b. 1960) entitled, pace Saint-Saëns, Le carnaval des animaux en peril. Given the recent focus in the news on endangered or even extinct species, this seems a rather timely, though perhaps odd, reinvention of the Baroque suite with these creatures in mind. It is easiest to tackle the older pieces first. Henry Purcell’s “Prelude for the Birds” from The Fairy Queen begins with a bit of cheeping in the background, and eventually the recorders have an antiphonal set of calls against a slow-moving ground. Jakob van Eyck (1590–1657) has an imitation of an English nightingale, an odd solo high recorder that meanders around, and one cannot help but notice that three minutes worth of this is a long slog, no matter how melodious. Theodor Schwarzkopf (1659–1725) inserts some bird calls in imitation in the violin solo as sort of ornaments in the Allegro and Gigue of his sonata, while François Couperin throws in a nightingale from his Pièces de clavecin, here done with a high recorder, though probably it was originally done by the harpsichord itself; this is more bird-like, though. For Jena-Baptiste de Bousset and Michel Blavet, why waste time with one nightingale when you can have two? Well, apart from the background noises, the music itself, drawn from a set of songs, is more like a countrified wander than imitation. When we get down to Michel Courrette’s bit from his pieces for musette, a country French bagpipe, the cuckoo appears as a counterpoint to a rollicking bucolic dance. Bouchot has arranged the Saint-Saëns bit from the Carnival for his ensemble, as well as the Britten piece, though the arrangement of the “Poules et Coqus” from the former has some recorded barnyard bits before the pecking motion of the instruments. The Ravel arrangement is quite melodious in terms of the various imitative calls. But the real focus of this work is the Bouchot suite. It begins with a languid prelude to a pangolin, which apparently is filled with sorrow, no doubt as a reminder that this creature may have been one of the harbors of the virus that caused COVID. There is even a bit of Chinese percussion. The Allemande is a sort of chromatic imitation of the gamelan of Java, while the courante is supposed to depict the dodo (whose image is ubiquitous on the booklet cover) with a strangely convoluted xylophone above which the recorder clucks a bit. The snowy owl or egret is said to be music in black and white, but the spare flageolet calls don’t really do much for the Sarabande nature of the movement, while the Gavotte depicting the Indian Gavial, a sort of crocodile, seems like the creature is perpetually drunk in the wobbly tune. Why one would have a sea cucumber doing a strange waltz is positively freaky, given their torpid state of existence. The suite concludes with a gigue entitled human being, which in its plaintive meandering style with harsh intrusive dissonances may indicate that we too may be about to become extinct. Perhaps, this gives food for musical thought. La Rêveuse is, of course, a good and solid performer of all of this stuff. The instruments, though, are on the eclectic side, as one might expect for the various bird calls required. The addition at times of actual birds (including chickens) can be a bit distracting, though it probably adds to the ambiance of the disc. The final suite is extremely modern, and while there is a zoological message contained in the titles, the actual music is stark at time, trippy at others, and filled with enough twists and turns that the actual Baroque dance foundations are mostly submerged. It is a strange disc, which some will find thoughtful and compelling, while others will merely wonder at the oddity. Moreover, some of the works, such as the van Eyck, go on far too long and so will be a distraction. Still, if you want something completely off the wall, maybe you could check this one out. Otherwise, caveat emptor.

|

|