Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

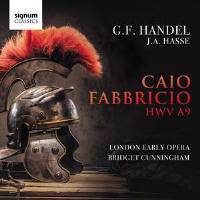

‘GF Handel’, the booklet confidently proclaims, with ‘JA Hasse’ nestling in smaller type below. Don’t get too excited, though. This is Handel the impresariocum-arranger, hastily concocting a pasticcio (‘hotchpotch’, ‘mishmash’, ‘pastry’ – take your pick) for the Royal Academy in 1733. Most of the arias come from Hasse’s Caio Fabbricio, premiered in Rome the previous year. Partly at the behest of his singers, Handel threw in a handful of arias by other Italians, from the famous Leonardo Vinci to the now-forgotten Antonio Pollarolo and Francesco Ciampi. His only creative contributions were new secco recitatives, briefer and tauter than Hasse’s originals. Set in Tarentum during the wars between Greece and ancient Rome, the quasi-historical plot of Caio Fabbricio is the familiar Baroque mix of power struggles, lust and treachery, with honour finally winning the day. Never a model of clarity, Zeno’s libretto suffered further from Handel’s cutting and pasting. To oversimplify, the high-minded Roman ambassador Caio Fabbricio is pitted against the ruthless Pirro (Pyrrhus), King of Epirus, who, spurning his betrothed Bircenna, has secret designs on Fabbricio’s captive daughter Sestia. Sestia’s lover Volusio, thought to be dead, vows to save her, and kill Pirro. After various twists, all is resolved, with Pirro pardoning Volusio, freeing Sestia and announcing that he will marry Bircenna. What the Royal Academy’s aristocratic audiences expected, and duly got, was a concert in costume from some of their favourite star singers. Virtuosity was the order of the day, with narrative coherence an optional extra. Hasse’s music is, as ever, euphonious and expertly crafted. His shapely melodies tickle the ear. But with their leisurely rate of harmonic change and uniformly homophonic textures (the whole opera is a counterpoint-free zone), the arias tend to sound too amiable for the dramatic situation. The first four numbers, all brightly tripping allegros in major keys and scored for strings alone, set the tone. Horns add welcome colour in a graceful minuet song for Bircenna and a ‘nautical’ bravura aria for Volusio. But listening without the text you’d often be hardpushed to gauge whether a character is rejoicing, baying vengeance or – as in Volusio’s blithely skipping ‘Varcherò le flebil onde’ – anticipating death. Bridget Cunningham, who has edited Caio Fabbricio for this premiere recording, draws neat and precise playing from her period band. Yet even in Hasse I sometimes wanted more tension in the accompaniments. Sestia’s outpouring of love to the condemned Volusio, ‘Lo sposo va a morte’, is a case in point. With her easily produced high soprano, Miriam Allan brings spirit, agility and shapely phrasing to each of Sestia’s four arias. Sharper Italian consonants would have made her performance even better. As Volusio, Anna Gorbachyova-Ogilvie – a new name to me – has a straight, rather instrumental timbre and sails merrily into the stratosphere in her ‘nautical’ aria. Again, though, her words can be hard to decipher. The singers in minor roles, including lyric baritone Morgan Pearse in Fabbricio’s single aria, all have fresh, youthful voices. Jess Dandy, sounding here like a deep, rich-toned countertenor, makes her mark in the cameo role of Pirro’s supporter Cinea. Pirro himself was sung in 1733 by the castrato Giovanni Carestini, who in the following seasons created the roles of Ariodante and Ruggiero for Handel. Exploiting the chiaroscuro within her warm, supple mezzo, Fleur Barron sings Pirro’s vocally wide-ranging solos with authority – tenderness, too, in an attractive siciliano by Pollarolo. I can’t imagine Caio Fabbricio reaching the modern stage. But if you have a taste for Hasse’s unfailingly mellifluous music – and don’t expect any Handel – you’ll find plenty to enjoy in a performance of skill, spirit and, where apt, virtuoso panache.

|

|