Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

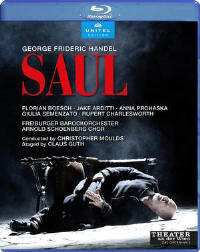

With its unflinching portrayal of the Israelite king’s descent into madness and terrible final lucidity, Saul is arguably both the richest and most disturbing of Handel’s oratorios. It is also fair game for a directorial makeover. In his Glyndebourne production conducted by Ivor Bolton, Barrie Kosky offered a portrait of a dysfunctional family that mingled violence with garish Hogarthian excess. In Claus Guth’s stark, claustrophobic staging at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien, set minimalistically between a bare dining room and what looks like a prison washroom, the Saul family are no less dysfunctional, with violence likewise an ever-present threat. The tormented elder daughter Merab, sexually attracted to David, seems to have inherited her father’s epileptic illness. David’s aria comparing Merab and her sister Michal (‘Such haughty beauties’) becomes a cue for an orgy involving the sisters, Jonathan and an initially bewildered David. Clutching Goliath’s severed head, David first appears as a vest-clad rustic, a holy innocent ill in a dazed world of his own, unaware of his sexual magnetism and his charisma for the crowd. By the end he has become Saul’s ruthless mirror image, heartlessly rejecting Michal and already showing signs of the epilepsy that has destroyed his predecessor. Symbolically, he smears his name in mud on the washroom wall, exactly as Saul had done near the opening. Saul himself, a ruler addicted to power, invariably clad in black, spends the oratorio either stumbling between rooms or writhing in agony on the floor. He stabs Jonathan, shockingly, at the end of Act 2 (David later follows suit with the Amalekite). Saul’s dialogue with Samuel becomes a baleful duet for one. The faintly sinister servant who hovers in the background in the earlier scenes morphs into an equally impassive Witch of Endor (chillingly sung by countertenor Rafa? Tomkiewicz), treating a crumpled Saul on a psychiatrist’s couch. Semaphoring ritualistically à la Peter Sellars (in his Glyndebourne Theodora), the adoring mob are stylised zombies. Only Michal, left bereft at the close, is unambiguously sympathetic. Guth’s unremittingly gloomy staging seems to have gone down well with the British and Austrian press. On the small screen, with frequent close-ups, its predominant darkness, in every sense, will be a handicap for many. As a concept I found it less theatrically compelling – and less sheerly entertaining – than Kosky’s Glyndebourne extravaganza. That said, the cosmopolitan cast, all accomplished stage animals, throw themselves with gusto into their roles. Although lacking the bass depth of Christopher Purves at Glyndebourne, Florian Boesch gives a comparably mesmerising portrayal of Saul: brooding, haunted, terrifying in anger, and colouring his words with a lieder singer’s subtlety (in immaculately clear English) in the Endor scene. The younger generation are equally well cast. All act vividly with their faces as well as voices. Jake Arditti, less silken in his prayer ‘O Lord, whose mercies numberless’ than Iestyn Davies for Kosky, deploys a bold, bright countertenor as David, and Rupert Charlesworth sings Jonathan’s music with a fine balance of metal and honey in the tone. There’s no danger here of Saul’s son being a passive cipher. If the sisters’ words in their arias are sometimes vague, they portray their contrasting characters with terrific energy. In Merab’s ‘Author of peace’, potentially a moment of cathartic healing, Anna Prohaska conveys a mingled desolation and sexual frustration. Her singing may not please Handelian purists. I found it hypnotic. Giulia Semenzato’s ‘In sweetest harmony’ is both sensous and radiant, an illusory vision of calm and family unity. Throughout, Christopher Moulds directs the incisive, full-bodied Arnold Schoenberg Choir, singing in near-faultless English, and the elite Freiburg band with dramatic flair. Orchestral detail, well caught in the recording, is closely observed, and tempo choices, usually on the mobile side, seem spot on. Moulds relishes Handel’s variegated colours. He uninhibitedly catches the brassy jubilance of the opening sequence, while the inexorable ‘Envy’ chorus and the magnificent tableaux that conclude each act unfold with cumulative power. With at least as fine a cast, Kosky and Bolton would still be my top DVD choice for Saul. But I’m glad to have seen and heard this Viennese production: for its engrossing individual performances, and for Guth’s dark, often wince-inducing take on a family in decay and the corrupting force of power amid ever-present brutality. |

|