Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

Reviewer:

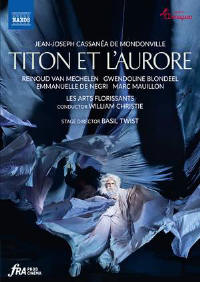

Richard Lawrence In Greek legend, the goddess Aurora (also known as Eos) successfully begs Zeus to make her lover Titon immortal, but fails to ask that he remain youthful. So Titon (Tithonus, as in the poem by Tennyson) grows older and more decrepit until he is eventually released by being turned into a cicada. But, like Isbé, Mondonville’s first opera (Glossa, 3/17), Titon et l’Aurore is a pastorale héroïque and our hero does not suffer so melancholy a fate. This recording was filmed at the Opéra Comique last year. One can only imagine how hard it must have been for the performers to play without an audience: they succeed brilliantly. In the Prologue, Prometheus rails against the gods and decides to bring clay statues to life, thereby creating mankind. Cupid (Amour), bewigged and in full 18th-century costume, enjoins mortals to devote themselves to sensuous pleasure. In the three acts that follow, Palès, goddess of shepherds, and Aeolus (Éole), god of the winds, try to end the love between Titon and Aurore, with whom they are respectively smitten. It is Palès who curses Titon, and he ages before our eyes (cleverly done, as he moves behind a succession of pillars). But Aurore is steadfast, and Cupid descends as deus ex machina: the curse is lifted and all’s well – even for Palès and Aeolus, who despite being written out after their duet in praise of revenge end up in this production with each other. Each act includes a divertissement (the prologue has two), which the director and designer Basil Twist exploits to the full with puppets: marionettes and, discreetly operated by human handlers, life-size models. Particularly enchanting are the sheep: Palès always has two in tow, but there’s an entire corps de ballet – troupeau de ballet, perhaps – that dances, flies, and at one point appears piled up in vertical rows like a couple of giant kebabs. The action proper begins with Titon anxiously waiting for Aurore. The slurred two-note phrases in the bass suggest a Lullian sommeil: clarification comes with the arrival of Aurore, goddess of the dawn, as the starlit sky gives way to rosy hues. Reinoud Van Mechelen, with his staff and floppy hat, makes a tender shepherd, the voice light but well up to the demands of his florid and lengthy ariette in Act 3, which he crowns with a ringing top D. His fellow Belgian Gwendoline Blondeel opens Act 2 in fine style with her sorrowful ‘Devais-je, Amour, de tant de larmes’ before her spirited rejection of Aeolus. Her ariette in Act 1 is rather overshadowed by a busily chirping flute. There’s a touching scene at the end, when the lovers dance the Rondeau en chaconne, closely observed by the sheep. Cupid doesn’t appear between the prologue and the finale, but Julie Roset sings with charm and has an excellent stage presence. Marc Mauillon is fine in the recitatives, which are more like ariosos, but when William Christie whips up a storm in the pit for the chorus of winds, ‘Sur les pâles humains que le tonnerre gronde’, both Mauillon and the chorus are lacking in power. As Palès, on the other hand, Emmanuelle de Negri is formidable in ‘Tu vas sentir les effets de ma rage’. Les Arts Florissants are in fine form, with expert scurrying from the violins and a beautiful bassoon in the all too brief prelude marking Cupid’s descent to sort things out. Another triumph for William Christie; two further performances are scheduled on July 8 and 9 at Versailles.

|

|