Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

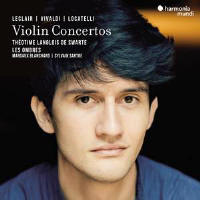

Reviewer:

Mark Seow I’ll start by getting all the bad things about this album out of the way. We are told that Théotime Langlois de Swarte plays on a Jacob Stainer ‘violin’ of 1665 but with an ‘archet’ by Pierre Tourte. There’s some questionable intonation in one ascending sequence in the final movement of Vivaldi’s RV384. There, that’s it: a single typo of language inconsistency in the booklet notes and two not even very dodgy bars. The rest of my job is much harder, if not the hardest task in the business: to describe excellence Alongside reviewing for Gramophone, I’m a baroque violinist and have been for just over a decade. Postconservatoire life, particularly in London, can be difficult: one gets sucked into a slew of Messiahs, the Passion circuit, the seemingly incessant rotation between Dido and Acis. For sure, there is joy in these patterns – the corporeal familiarity of fingerwork, a smile between desk partners when it gets to that harmony. But it can be stultifying, too. Théotime Langlois de Swarte reminds me why I fell in love with the Baroque violin in the first place and chose to lead a life on gut. His playing is joyful; it is wild and beautiful, inventive and efficient. L’arte del violino, published in 1733 in Amsterdam, I was surprised at how little there was in the musical notation. Langlois de Swarte’s ornamentation – swerving, bluesy, capricious – does what so little recorded ornamentation manages to do: it sounds utterly improvised and untethered to ink. Sucked back into the oily torrent of the orchestral tutti, Langlois de Swarte’s closing statements sketch out a cadenza that comprises not so much notes as moonlit vapour. Really, that choice of track was arbitrary. Keep going and in the concerto’s final movement, Allegro – Capriccio, you’ll encounter dizzyingly good playing. Les Ombres produce a luxuriously fine sound; and spearheaded by cellist Hanna Salzenstein – and a gorgeous amount of bassoon! – the drama never ceases. All the while, Langlois de Swarte is an acrobat of double-stops, joyful arpeggio flicks, G-string kicks and a written-out cadenza of astonishing virtuoso ability. For one acquainted with this particular passage, the apparent ease with which Langlois de Swarte trills with his fourth finger simply defies belief. Langlois de Swarte first caught my attention duetting with lutenist Thomas Dunford on their album ‘The Mad Lover’ (12/20). The pair brought us an account of aching melancholy, but it was the violin-playing that grabbed my ears. I described his ‘seething virtuosity’ and ‘seductive fury’, concluding that ‘I might very well be in love’. Well, with this new recording I’m ready to scratch out that ‘might’. We’ve since also had his recital album ‘Proust, le concert retrouvé’ with pianist Tanguy de Williencourt (Recording of the Month, 5/21). Reviewer Tim Ashley was practically giddy, too: ‘a breathtaking, astonishing disc, and I cannot recommend it too highly.’ Langlois de Swarte, I’m not scared to write, is the real deal. If you want to sample this album’s stunning array of delights, go straight to the Largo of Locatelli’s Concerto in E minor. The strings churn like a stomach filled only with coffee. Langlois de Swarte enters with laser intent, and so we might think we’ve heard this before: a soul-baring Baroque aria. But this diva is immediately malleable, retreating into wistfulness for the relative major and tenderly feeling out the spaces between the harmonies. When checking against Locatelli’s L’arte del violino, published in 1733 in Amsterdam, I was surprised at how little there was in the musical notation. Langlois de Swarte’s ornamentation – swerving, bluesy, capricious – does what so little recorded ornamentation manages to do: it sounds utterly improvised and untethered to ink. Sucked back into the oily torrent of the orchestral tutti, Langlois de Swarte’s closing statements sketch out a cadenza that comprises not so much notes as moonlit vapour. Really, that choice of track was arbitrary. Keep going and in the concerto’s final movement, Allegro – Capriccio, you’ll encounter dizzyingly good playing. Les Ombres produce a luxuriously fine sound; and spearheaded by cellist Hanna Salzenstein – and a gorgeous amount of bassoon! – the drama never ceases. All the while, Langlois de Swarte is an acrobat of double-stops, joyful arpeggio flicks, G-string kicks and a written-out cadenza of astonishing virtuoso ability. For one acquainted with this particular passage, the apparent ease with which Langlois de Swarte trills with his fourth finger simply defies belief. The playing throughout is so excellent – from Langlois de Swarte and Les Ombres – that there is not much else to say. These are performances so special that I feel a changed man from listening to them. Buy it, tell all your friends: if you’re lucky, this recording will clamp on to you like a barnacle to a boat. It will infuse your life with joy. It might even make you believe again.

|

|