Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction |

|

|

Reviewer:

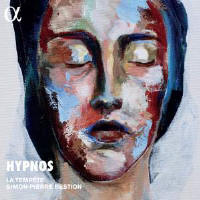

Fabrice Fitch La Tempête’s projects always give one plenty to think about. Here their subject is sleep and its metaphorical adjunct, death, but also trancelike states. The programme mixes early and contemporary music in a way that seems to have gone out of fashion, and though not all the newer music is to my taste (being predominantly on the trippy side), the coherence of the programming is not to be gainsaid. Simon-Pierre Bestion’s take on historically informed performance is complex, to say the least, and hard to summarise in a review of this length. To take the most obvious example: his vocal ensemble of 10 singers is accompanied by just two instruments, a cornett (usual) and a bass clarinet (not so usual). In the right acoustic, the latter substitutes nicely for a bajón to double the basses, but it can also flare up, its rich tang standing out suddenly and adding fatness and a grit that takes you right outside the acoustic frame of reference in a way that’s pleasingly unsettling. At one point (in one of the verses of Anchieta’s Libera me), it plays in the same range as the cornett in a duo, and this too is very effective. It almost makes you forget that the stylistic relationship of these verses with Anchieta’s polyphony is deliberately tenuous, consisting mostly of dissonances. But Anchieta does not set the verses himself: they would have been sung in chant, which would have been ornamented polyphonically. So one cannot say that style has been deliberately ignored, just stretched – how much depends on your point of view. Finally, by some strange alchemy, it can sound as though there are more accompanying instruments than there actually are (so often a mark of the best chamber music). All this should be enough to prick the curiosity of all but the most closed-minded of Renaissance music enthusiasts. I especially enjoyed the female soloist in the chanted Dixit Dominus; but might it have been even more striking without the drones? Bestion’s singers are very flexible, and frequently superb. They can adopt the style (not to say the mannerisms) of Ensemble Organum, whose director, Marcel Pérès, has plainly had a great influence on Bestion; they are equal to Scelsi’s quartertones; and they can sing ‘straight’ when needed. These stylistic shifts are not jarring, though Bestion’s aesthetic stances are not always as free as he might claim. I have no quarrel with his stated wish to distance himself from the English choral sound in his interpretations of Renaissance music but I don’t see why the ornaments typical of Pérès or Graindelavoix need always entail the ‘goatherd’ approach to vocal timbre, which is more likely to keep you awake than the opposite. But the fact that this recording raises complex aesthetic issues is part of what makes it valuable. The presentation leaves some useful information out, however: half of the Gloria from Pérès’s Missa ex tempore is a gloss on the same section of Ockeghem’s Prolation Mass, and the texts in the booklet are not all complete. |

|