Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

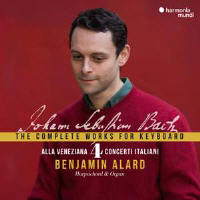

Reviewer: Philip Kennicott With his fourth volume devoted to the complete keyboard works of Johann Sebastian Bach, Benjamin Alard reaches the middle to later years of the composer’s Weimar period. The younger of the Duchy’s two joint rulers, the short-lived Johann Ernst III, seems to have been the vector whereby the music of Vivaldi and other Italians swept through musical circles during this period, with copies of the Venetian composer’s Op 3 (L’estro armonico) and Op 4 (La stravaganza) concertos likely purchased in Amsterdam. So, after devoting his previous volume to early French influence, Alard now turns to the Italians, including the complete Bach transcriptions of Vivaldi’s concertos, the Marcello Oboe Concerto (with its gorgeous second movement a staple of contemporary Baroque programmes) and Bach’s well-emended transcription of Prince Johann Ernst’s effort in the form. Alard’s booklet note stresses both Bach’s frequent interventions in the musical re-composition process from string ensemble to keyboard and Bach’s tacit invitation to the performer to take liberties in the interpretative act. ‘The further we progress chronologically through Bach’s works, the less we will have this feeling of freedom,’ writes Alard, ‘because he increasingly assembled his pieces in collections and composed for published editions (like The Well-Tempered Clavier or the Six Partitas) where everything is marked in the score, thought through from A to Z, the right note written at the right point.’ Alard indulges this freedom in his choice of instruments, including performing several of the organ concertos on the pedal harpsichord (a robust 1993 instrument based on a 1720 original from Hamburg). He is also free with his choice of registration, to emphasise the contrast between solo and tutti lines, and his ornamentation, especially florid in slow movements with cantilena lines. The richness of his embellishments to the solo oboe line in the Marcello suggests a kind of aural substitute for vibrato, giving the melodic line a shimmering, quavering, vocal-like intensity. This is charismatic music; and if it isn’t played more often that is likely due only to the vestigial remnants of the mid-20th century’s prejudice against transcription. Interspersed with the concertos are several of the choral preludes and the magisterial Toccata in C, BWV564, played on a pleasingly hooty 1710 Andreas Silbermann organ from the Abbaye Saint-Étienne in Marmoutier. |

|