Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

||||

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

||||

|

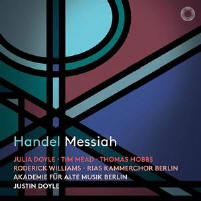

Reviewer: William

J. Gatens

There is no such thing as a

perfect recording of Messiah. I doubt that any two critics could agree on

what that would be like. Most period- instrument recordings simply annoy me.

One of the few that does not is the 1988 recording by Trevor Pinnock and the

English Concert (DG). I like his dignified pacing and the refinement of the

playing and singing. Even so, there are things that could have been better,

and I have spoken with colleagues who don’t much care for that recording.

The trouble is that so many conductors, when faced with such a familiar and

often-recorded work, seem to feel obliged to leave their individual mark so

as to stand out from the crowd. This may be unfair to many interpreters, but

I do not think it my imagination that many eccentricities are foisted on

this masterwork that would not be if it were less well-known. Here again, I

like Pinnock because he plays it down the middle. The purpose of this

preamble is to give some context to my judgement that the present recording

contains much to recommend it.

The singers and players are

first rate. Justin Doyle presides over some remarkably crisp and clean

playing and singing. He favors brisk tempos, sometimes faster than I would

like, but rarely to the point of eccentricity. Of course, his singers and

players are undaunted by such tempos. ‘For Unto Us a Child Is Born’, for

example, is taken very quickly, but it comes across as buoyant and jovial,

not driven. The four solo singers leave nothing to be desired in terms of

vocal technique and poise. I was quite taken with the mysterious quality

bass Roderick Williams imparts to ‘For Behold’. Without wishing to slight

the others, I was especially impressed with countertenor Tim Mead. The male

alto voice is an acquired taste, but Mead’s tone is solid and commanding and

unlikely to sound exotic to listeners more accustomed to contraltos. All

four soloists freely ornament their lines, especially on repeats. Not all of

the ornamentation is equally effective or convincing. Sometimes I think they

just enjoy singing notes that are not on the page. For me the worst instance

is the da capo of ‘The Trumpet Shall Sound’, where Williams’s elaborations

sound contrived and too busy.

The recorded sound is

remarkably clear. In my reviews I often complain that the solo voices are

overbalanced. Here the opposite is the case; the soloists sound artificially

prominent. There has to be a happy medium. The choir of 34 voices has good

presence but sounds distant compared with the soloists and wrapped in an

acoustical cloud. Instead of conventional program notes, the booklet

contains a highly amusing imaginary conversation between Handel and his

librettist Charles Jennens written by Roman Hinke. He exhibits the

cantankerous personalities of both gentlemen, and manages to get in a good

deal of historical information along the way. Deliberately anachronistic

turns of phrase liven the prose, and the subject matter is not limited to

the lifetimes of the two speakers. For example, Handel is permitted to

deplore the gigantism of the Victorian Handel Festivals at the Crystal

Palace, where Messiah would be presented by thousands of singers and

players. This may not be the Messiah recording all

the world

has been waiting for, but one could do a whole lot worse. | ||||

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

||||