Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Charles

Brewer

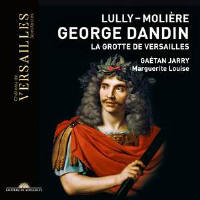

Between 1664 and 1666, Louis

XIV had an artificial cave built at his country chateau, Versailles, but

demolished it in 1684 to allow construction of the north wing. Soon after

its completion, this grotto became the setting for Jean-Baptiste Lully’s

first collaboration with the poet Philippe Quinault, Le Grotte de

Versailles. This “eglogue en musique” was first performed at Versailles in

1667 or 1668 and was still being performed (with some alterations) as late

as 1728 at the Concerts Spirituels.

As a typical divertissement,

it begins with a French overture, followed by songs and dances. The center

point of the eclogue is the entry of Daphnis and the Nymphs, who were joined

in the dance by Louis himself, and it concludes with an extended “echo”

chorus and dance. This is the second complete recording I know; the earlier

was by Hugo Reyne with La Simphonie du Marais (Accord 461811, 2001). Both

reflect a sensitivity to the nuances of the French style, though the soloist

for Iris in 2001 seems more comfortable with the intricate ornamentation

written in the manuscript for the second verse of her lament. Unfortunately,

the musettes mentioned in an original libretto are missing in both

recordings, both of which attempt to recreate the original performance.

Molière’s “comedie en musique”, George Dandin, was first performed at

Versailles on 18 July 1668 with Lully’s incidental music. This

divertissement was just one part of an extensive evening’s festivity,

incorporating appetizers, wandering through the gardens, the play in a

specially constructed outdoor theater, a large dinner followed by dancing

and fireworks. The plot follows the plight of the rich peasant, George

Dandin, and his unfaithful wife, and the libretto was conceived “in

the manner of an improvisation” with inserted interludes that form a

miniature pastoral. These are now missing from most modern editions of

Molière’s play, but this recording includes both the music that preceded the

play, the two interludes between the three acts, and the final

divertissement with its concluding double-chorus dialog between the

followers of Bacchus and Love. | |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|