Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Raymond

Tuttle

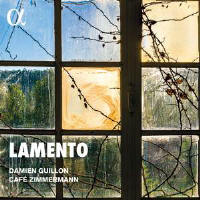

We hear complaints all the

time about the dearth of singers, in these days, who can do justice to

Puccini and Verdi. Do these complainers realize that we are living in a new

golden age of countertenors? Not a month goes by, it seems, without a new

one coming to the fore. Guillon is not “a new one,” for he has been making

recordings for more than a decade, but he is new to me. After having heard

Lamento, I will be on the lookout for his upcoming discs, much as I am on

the lookout for those by Philippe Jaroussky (three years older) and Jakub

Józef Orliński (a decade younger), for example. One of the things that makes

Guillon different is that he also is active as a conductor. In 2009, he

founded the early music ensemble Le Banquet Céleste, which encompasses both

singers and instrumentalists, and they have made several recordings

together. I think this is Guillon’s first recording with Café Zimmermann, a

group that is more attentive to German repertory. (He has, however, recorded

several Bach discs with Le Banquet Céleste.)

This program presents Guillon

as a soloist, alternating with purely instrumental works. On the whole,

textures are frugal and the mood is restrained and sincerely devout—there is

neither breast-beating nor wallowing in pity for self, or for others. For

example, the program ends with the seven-minute Passacaglia for solo violin,

a movement which in turn ends Biber’s Rosary Sonatas, music that is even

purer and more spare than the Chaconne from Bach’s Solo Violin Partita No.

2. The vocal works similarly emphasize purity and simplicity; piety and

submission are the expressed both in the texts and in the music.

The purity and simplicity of

the vocal works are emphasized by their rarity; this is not music I recall

being exposed to previously. Johann Michael Bach was Johann Sebastian Bach’s

first cousin once removed, and also his first father-in-law; Johann

Christoph Bach was Johann Sebastian’s uncle. These composers are more

familiar for their family name than for their music. Even more obscure is

Christoph Bernhard (1628–1692). He spent most of his career in Dresden—part

of that time under the influence of Schütz. It is Biber, represented by the

most works on this CD, who comes off as the most memorable composer here,

although nothing on this CD is totally devoid of interest or appeal.

Among the instrumentalists, it

is violinist Pablo Valetti who leaves the strongest impression, thanks to

his performance in the Biber Passacaglia (I presume) and elsewhere. As for

Guillon, it is perhaps unfair to judge him solely on the basis of this

program, which was not designed to show off the widest range of his talents

and capabilities. That said, his sound, while not large, is gravely

beautiful, stylistically sensitive, and underscored by his obvious

intelligence and scholarship. I look forward to hearing what else he can do

with these resources! Lamento operates within rather narrow boundaries, and it is a tribute to these musicians that the music runs out before our patience does. Most listeners will be impressed with the beauty of these performances more than they will be by the music itself.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|