Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

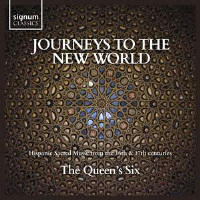

The Spanish

were quick to capitalize on the conquista during the 16th century on both

the Central and South American continents. The military commanders were

accompanied by monks from the various sects, Franciscans and then

Dominicans, all of whom were fired with the zeal to Europeanize these lands.

Never mind that both Cuzco and Tenochtitlan were more advanced than Iberia

in terms of infrastructure and socio-economic culture (though they did have

a distressing tendency to rip the beating hearts out of captives in

religious rituals); the old ways had to go and be replaced by Catholicism

and a Viceregal structure. This happened almost immediately, though the main

cathedrals in both places were superimposed right on top of the old temples

and pyramids. Moreover, new cities such as Lima were settled as major

centers, and so New Spain (in aggregate) rapidly expanded. Part of the

conversion process was the use of music, recognized because the musical

environments of Meso-America were already well-developed pre-conquest, and

thus the switch to choral music of the new religion brought from Europe was

not difficult; and when works began to be composed in the Americas, they did

not exclude use of indigenous melodies and rhythms. This disc provides a nice compendium of the sorts of music that were imported from Iberia, mainly through the port of Cádiz. Some of the composers were already well known to European centers, such as Cristóbal de Morales and Tomás Luis de Victoria, while some of the other lesser-known composers, such as Hernando Franco (1532–1585), Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla (1590–1664), and Miguel Mateo de Dallo y Lana (1650–1705), all immigrated to New Spain, where they served in the cathedrals there. Thus the music written for the venues was a mixture that carried on the Iberian traditions. The music was mainly a cappella, as this and plainchant were the most recognized sacred formats of the time, even though by 1650 instruments were becoming more common in the Viceregal churches.

Morales’s

Regina cæli, for example, is a good example of the contrapuntal flow as

common practice of the style of Josquin, with the voices weaving about each

other. While compact, the Salve Regina of Franco provides variety by

dividing the sections between chant and a fluid Palestrina-style polyphonic

texture. The motet Verbum est in luctum is also found in two versions on

this disc. The first by Alonso Lobo (1555–1617) was composed for the funeral

of Philip II and is in a solemn work in which the textures increase in close

suspensive harmonies, though with some scaffolded entrances among the

seamless texture. Padilla also set the work for Puebla, with his more treble

dominant, but using the same style of voice parings and entrances, a device

common for the period. As this comes later, it is not surprising that there

is a hint of more homophony and textural depth than Lobo. Another example of

the emotional depth to be found is in the motet In horrore visioniones by

Francisco López Capillas (1614–1674), an instrumentalist at the main

cathedral in Mexico City. Here the voices are more soloistic, with closely

aligned harmony and short but seamless integrated phrases that seem to float

languidly. As the notes state, the motet Beatus Achacius by Francisco

Guerrero (1528–1599) is for a martyr who somehow has been dropped from the

row of saints as only a mythological figure. Why Guerrero, who worked in

Seville, would have chosen this odd text is unknown, though his own travels

to the Levant may have helped him become acquainted with the story, given

the Achacius was killed in that region. In any case, the smooth counterpoint

develops in cautious steps, and the tone is quite mysterious. More uplifting

is the motet O quam suavis est by Lobo, with its ethereal suspensions in the

upper register. While such music might not be everyone’s cup of tea, as it is thoroughly contemplative in nature, it presents an excellent cross-section of the sort of a cappella sacred works that were common on both sides of the Atlantic. The music composed in New Spain is no pale imitation of that of the Iberian homeland, but rather the similar styles show that the musical needs of the churches in both places were quite the same. Indeed, the counterpoint of those pieces that predate the Council of Trent is much the same as those that postdate it, so that one has a musical continuum. Unlike the rather harsh and unyielding sounds of the Old and New Worlds disc reviewed in this issue, the smooth and well-integrated vocal textures of The Queen’s Six show how this music reflects purity of sound, easily negotiating the solemn moods and complex counterpoint of the originals in a pure fashion. This is an excellent disc, and while contemplative sacred music may be more of an acquired taste in our frenetic world, these pieces show how music can be ethereal and calm. Well worth obtaining.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|