Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

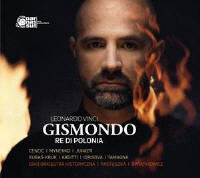

Reviewer: David Vickers Gismondo re di Polonia (Rome, 1727) depicts an entirely fictitious title-hero’s multiple acts of clemency towards the rebellious Lithuanian duke Primislao. The libretto was dedicated to James III of Great Britain; the Old Pretender lived close to the theatre and was married to a Polish princess. This recording inaugurates the new label Parnassus Arts – Max Emanuel Cencic’s production company that has already spearheaded pioneering recordings of Vinci’s Artaserse (Virgin/Erato, 1/13) and Catone in Utica (Decca, 7/15) with all-male casts featuring assorted countertenors playing female characters. This time around experimental casting has been shelved: alongside four countertenors, there are three female sopranos. Co-directed by the violinist Martyna Pastuszka and harpsichordist Marcin S´wia˛tkiewicz, the Polish band {oh!} Orkestra Historyczna crackles with vigorous theatricality. The Sinfonia bursts with full-throttle energy and tension – and this is how arias are played too, although there is sophistication and subtlety when required. Recitatives have fulsome continuo realisations that roll and thrust extrovertly. Aleksandra Kubas-Kruk’s stratospheric embellishments and shooting up an octave at cadences are displayed in Primislao’s implacably tempestuous ‘Nave altera, ch’in mezzo all’onde’, and a call to arms with a pair of trumpets and oboes (‘Vendetta, o ciel, vendetta’) has swaggering bellicosity. Gismondo’s daughter Giuditta has a secret crush on her father’s enemy; her arias are sung with sparkling personality and dizzying embellishments by Dilyara Idrisova. Cencic’s cantabile phrasing is to the fore in Gismondo’s ‘Sta l’alma pensosa’, and the bustling heroic showpiece ‘Torna cinto il crin d’alloro’ packs a visceral punch. Ernesto’s outrage when diplomacy fails (‘Tutto sdegno è questo core’) matches bustling strings, rushing bassoon and punctuating horns with Jake Arditti’s lively coloratura, whereas his evocation of hopeless love (‘D’adorarvi così’) has honeyed sweetness (the top ‘violini’ stave played solo by Pastuszka). Nicholas Tamagna has very little to do as the vengeful schemer Ermano, but does it well. The adversities of star-crossed lovers Otone (Gismondo’s son) and Cunegonda (Primislao’s daughter) inspire Vinci’s most memorable scenes. Sophie Junker’s range of dramatic expression is demonstrated in Cunegonda’s heartbroken assumption that Otone has been treacherous towards her father (the F minor lament ‘Tu mi tradisti, ingrato’, with bassoon and four-part strings, marked senza cembalo), the uttering of a vicious curse on her father’s enemies sworn in front of a statue of Otone (a violent ombra accompanied recitative ‘Eterno, memorabile’), her crazed grief upon believing her father has been slain in battle (the accompanied recitative ‘Misera! Ah sì, ti veggo’), and venomous hysteria hissed towards the innocent Otone in the tumultuous D minor rage aria ‘Ama chi t’odia, ingrate’. Otone’s pastoral ‘Quell’usignolo’ is sung by Yuriy Mynenko with sensitive delicacy, while a pair of sopranino recorders imitate a nightingale over almost imperceptible long horn notes (S´wia˛tkiewicz’s extemporised harpsichord soloing is a touch busy), and an F major lament featuring two bassoons (‘Vuoi ch’io mora?’) is performed sublimely; Mynenko’s bolder virtuoso side is unleashed in the valorous ‘Assalirò quel core’ (featuring flamboyant horns). The emotional core of Acts 2 and 3 reconfirm Vinci as the foremost Italian musical dramatist of his generation. |

|