Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

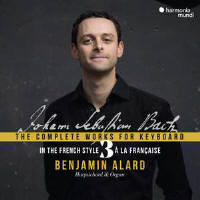

This is the

third volume of the documentary complete keyboard works of Johann Sebastian

Bach. This one is entitled In the French Style, meaning that it purports to

be a compendium of pieces written in the particular Baroque national style,

spread out among three discs and performed on both the harpsichord and organ

by Benjamin Alard. This set also includes a number works by other composers

that Bach himself either appreciated and/or copied.

For a complete works in the “French” style, this is quite a list, but one should realize that many of these pieces are in fact chorale preludes or improvisations, and thus one might be tempted to questions whether they are French at all. In the interview published in the excellent booklet notes by Peter Wollny, Alard dodges the first question by noting that French music was in vogue in Weimar and that Bach had copied out French dances while still a student. He then goes on to speak mainly about the instruments used and how the dances in the conventional suite of the time were influences. This is as may be, but when one looks at the music in this set, much of it appears to be more generic for the time rather than reflecting a national style, no matter what was in fashion. Even including some extraneous works by Bach’s contemporaries François Couperin and Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer (1656–1746), or organ works by Nicolas de Grigny (1672–1703) and André Raison (1650–1719), doesn’t really show much in the way of musical correspondence with Bach’s works, though I admit this is only an opinion and he is known to have appreciated the music of, for example, Couperin.

On to the

music, one needs to separate the pieces out a bit. As for the suites, there

are eight of them in this set. A couple are in fact part of the English

keyboard suites, BWV 806a, 807, and 809 all were collected for this group,

though Wollny does note that these three, along with BWV 996, formed part of

a series that predate their grouping. A couple of samples are interesting.

In BWV 807, the Sarabande is gentle, with a few rather interesting harmonic

twists, here performed with considerable depth. This is followed by the

double bourrées, which are energetic and precise in their almost manic

non-stop performance in the first but with a more measured approach in the

second. Of course, this concludes with a rather severe gigue. The Suite

“aufs Lauten Werck” (I used the modern German in the content above) was

originally written for a special harpsichord stop, and the opening prelude

has an improvisatory feel about it, with tempos that are like a fantasia in

their variability, as well as rolling chords and flashy sweeps of notes.

This goes into a rather jaunty dance section before the slower portion

returns, as in a French overture format (quite common for the period). Here

I rather like the mysterious and pompous Courante, with its deeper

registration.

The more

conventional suites (BWV 820 in F Major and BWV 819 in E♭) seem more

stereotyped as to structure. The first Overture seems almost as if it could

have been orchestrated, while the Entrée is quite French in its stately

march dotted rhythms, but the minuet that follows seems to me to be almost

like an ostinato, and the concluding gigue could easily have been written by

Bach’s friend Telemann in its lively and entertaining rolling melodic line

and rather abrupt ending. The short F-Minor Suite (BWV 823) is almost like

an unfinished torso of a suite, with only three movements. The opening

prelude is rather flowing with a clearly defined theme, and the Sarabande is

quite introspective, while the concluding gigue literally wanders about.

As for the

single works, the three short minuets from the Wilhelm Friedemann Notebook

are all simple, direct, and intended as both compositional and performance

studies. These works (BWV 841–843) are not intended as more than models. The

Praeludium (BWV 921), however, is a tour de force, with rolling textures, a

fantasy variable tempo, and considerable harmonic depth, even when suddenly

short aria-like interludes intrude.

Disc 2 is

devoted to the organ works, but here there is only the idea that Bach used

some of his French colleagues’ models for his own counterpoint. For example,

he creates a rather thickly textured variations on Couperin’s harpsichord

piece (BWV 587), and the C-Minor Fugue (BWV 546/2) is about as gnarly a

subject as one could expect and there is little that indicates any French

origins. The remainder are mostly chorale preludes, where Bach’s legendary

organ improvisations take on new life; again, very little “French” here,

though these variations on the chorale “Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr”

indicate his highly vaunted ability at taking a tune and creating a

magnificent sound edifice thereof. I’ve glossed over the intrusions by Bach’s contemporaries, for while they may have had some inspirational fodder for his own works, they clearly are rather secondary in terms of style and complexity. As for the performance, Benjamin Alard has a clear knack for recreating Bach’s own well-documented performance style. His phrasing is clear, his choice of registrations both convincing and appropriate to the individual movements, and his interpretation second to none. This is not just a documentary set among other volumes, but rather in its own right a powerful performance of music that ranges from little known to traditional repertory. My advice, if you want to hear Bach that goes beyond into the realm of the sublime, even in the simpler pieces, this is one set for you.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|