Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Peter

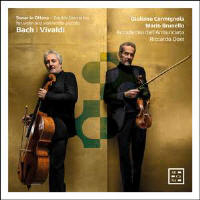

Loewen The program consists of double concertos by Vivaldi and JS Bach flanking Johann Gottlieb Goldberg’s Sonata in C minor (Dürg 14). The title of the recording Sonar in Ottava aptly describes the relationship between the two solo instruments playing an octave apart. The “Violoncello” article in the New Grove says the definition of violoncello piccolo is in some dispute, because it appears a number of 18th-Century instrument makers, including Stradivarius, experimented with a variety of designs for a violon (i.e. large fiddle) that could play virtuosically in the tenor range. These experiments gave us the viola pomposa, viola da spalla, and the violoncello piccolo.

Bach calls for a violoncello piccolo, tuned an octave below the violin, in the scores for several of his cantatas. Bach appears also to have experimented with instrumentation elsewhere. For example, many of his concertos for one or two harpsichords are adaptations of concertos he had composed for violins or oboe. It is in this 18th-Century spirit of adaptation and experimentation with instruments that one should appreciate the music on this recording. The two concertos by Vivaldi (RV 508 and 515) were composed for two violins, as was Bach’s concerto S 1043; the concerto S 1060 for two harpsichords was originally conceived for violin and oboe. Hearing them on violin and violoncello piccolo, playing an octave apart, gives one a different appreciation of sonority in these familiar concertos. I am impressed particularly with Brunello’s achievement. This repertory is challenging for violinists. The four-string violoncello piccolo often plays essentially the same music as the solo violin on this program, only an octave lower, so imagine playing this repertory on a fingerboard twice as long as the violin’s. It takes bit of adjusting at first, but it is very pleasant hearing the two instruments blend so well. Of course, the fast movements are impressive, because the technical achievements of each soloist are on full view; but I find the slow movements more engrossing because one can more readily appreciate how Bach’s and Vivaldi’s music sounds when transposed to a lower range. The middle movements of Bach’s Double Concertos are sublime. On the one hand, one might miss the delight of hearing two instruments playing in close proximity of pitch. One cannot help but think that listening to instruments playing “apart” is a bit like like watching two figures dancing just out of range of each other. Yet, at the risk of straining the imagery, hearing the violin and violoncello piccolo echo the familiar phrases of these slow movements makes them sound a bit more like tender love duets between male and female figures.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|