Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|

|

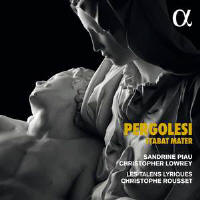

THE MUSICIAN AND THE SCORE Pergolesi’s Stabat mater

Pergolesi was, it seems, already terminally ill with tuberculosis when he accepted the Stabat mater commission from the Neapolitan confraternity of Cavalieri della Vergine dei Dolori for its annual Lenten services in the church of San Luigi di Palazzo. According to the composer’s first biographer, the Marquis of Villarosa, the work was completed on Pergolesi’s sickbed at a Franciscan monastery in Pozzuoli shortly before his death (aged only 26) in 1736. He bequeathed the autograph score to the royal chapel organist Giuseppe de Majo, and it passed through several owners for a few generations before it ended up in the library of Montecassino Abbey. A facsimile of Pergolesi’s original manuscript is available, and I wonder if Christophe Rousset has looked at it. He laughs, nonchalantly: ‘Yes, I did! But there was nothing valuable in it. We use a good edition by Helmut Hucke [Breitkopf & Härtel, 1987], and I’ve only ever found two incorrect notes in it.’ It soon becomes obvious that Rousset knows this score inside out. I wonder if his approach to performing it has changed since he recorded it for Decca back in 1999 with Barbara Bonney and Andreas Scholl. ‘I would like to say no – but it probably has, yes! I didn’t want to consciously change my views because I have to be honest with the piece, and its flow should be a certain way. But it is one of the most performed pieces in Les Talens Lyriques’ repertoire. We’ve done it something like 50 times around the world, with many different singers, and that probably means it has evolved somehow. This music is very theatrical and expressive, so when there is a change of singers – it’s Sandrine Piau and Christopher Lowrey in the new recording – the sound and emotional content of the piece will be communicated in totally different ways, even if the core of my conception remains consistent.’ Rousset remains adamant about the importance of full-length appoggiaturas rather than snappy quick passing notes. ‘In the past when we’ve done this piece I had arguments with some singers because I insist on long appoggiaturas – not just because it’s a matter of personal taste but because it is a rule recommended by Neapolitan solfeggi of the time. For such music that expresses pain and beauty, the point of the appoggiatura is the dissonance that expresses the crucial emotions of the words.’ Rousset’s perspective as a harpsichordist comes to the fore when he draws my attention to the tread of the walking bass line in the opening Stabat mater dolorosa. ‘Continuous quavers running in the bass can’t all be played exactly equally; it is vital that the curve for all the instrumentalists reaches its peak in the fourth bar of the phrase, which means enriching the length of the quavers where the chromaticism of the second violin comes down. Also, the staccato first violin notes and slurred notes in response all represent the nails being driven into Christ’s hands and feet. There is musical refinement, but also pain and grief – reinforced by moments of suspense when there are rhetorical silences after interrupted cadences.’

The third

movement, O quam tristis et afflicta, is another duet featuring harmonic

twists and fermatas producing poignant silences after phrases. Rousset points at

how diminished sevenths ‘convey the tension of the drama – this represents

“affliction”; and then in the next phrase we move from G minor to B flat major

as it describes the tenderness of Christ smiling towards his mother – for this

transition Other movements require vigorous energy. Rousset sees the quick Quae moerebat et dolebat as ‘full of symbols – the syncopations are a way of describing the nails in Christ’s hands on the Cross. If you do just an elegant interpretation, the images behind the music lose their purpose.’ After a solemn start, Quis est homo qui non fleret transitions into a quick allegro at the text ‘Pro peccatis suae gentis’. Rousset mentions, ‘I do it very fast because of the “flagellis” – the whip strikes here on every beat in the bass.’ Another extrovert moment is the animated duet Fac, ut ardeat cor meum, and it is the most densely contrapuntal music in the entire piece. Rousset agrees, pointing out that its tension ‘is about the fact that “ardeat” is fire. It shows what a good contrapuntist Pergolesi was. When we hear Neapolitan opera of the period, there’s a risk we might think its just decorative and galant, based on a nice line of singing, but actually all the pupils in Naples conservatoires were trained in counterpoint to a really high level and were able to write a fugue – composers and even castrati!’ We look at the exposed instrumentation and the expression of fragility in the sublime finale, Quando corpus morietur. Rousset confirms, ‘Heartbroken vulnerability is the point. The short notes in the bass and violas are all about the movement of breathing and sighing. Its important that the bass notes on the organ are not too short, just detached and clear enough to give this idea of sobbing in rhythm, and then the second violins play sighing figuration – but the first violins’ part is sostenuto and very lyrical. The introduction is actually more lyrical and cantabile than anything in the singing lines here!’ Dolorous sincerity and contrapuntal skill are set alongside contrasting movements of sunny tunefulness in E flat major that can sound incongruously cheery. In careless hands, these moments might not seem penitent enough for Lent, but Rousset observes that Pergolesi’s stile galant Neapolitan aesthetic is never merely about prettiness. He points out that the graceful Sancta mater, istud agas ‘is about the inner soul. You can have the pain of the Virgin, and the agony of Christ on the Cross, and so on, but there’s also amazing beauty. If you look at Italian religious art, you can recognise the grace of Mary and also feel tenderness for her.’ The parallels between Pergolesi’s Stabat mater and visual aesthetics lead us to discuss the Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Rousset suggests, ‘Although it’s about a century too early, the Ecstasy of St Teresa has this southern Italian way of conveying sensuality – that you can enjoy the pain in rapture.’ He also shows me an image of the Sicilian rococo sculptor Giacomo Serpotta’s stucco depiction of a voluptuous, breastfeeding Charity, in which she is recognisably human rather than pristinely angelic. Rousset explains: ‘I’m fond of not having pure angels singing in sacred music. If the song of the Virgin or God is recognisably human, it becomes close enough for us to recognise ourselves, and the more touching the message is.’

|

|