Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|||||||

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|||||||

|

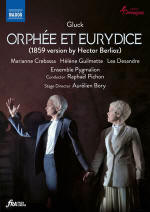

Reviewer:

Richard Lawrence Opera directors today seem to have difficulty in coping with Gluck’s retelling of the Orpheus legend, where – in both the Vienna version of 1762 and the Paris reworking of 1774 – the lovers are reunited after Eurydice’s second death and all ends happily. Recent productions on DVD have shown Orpheus wandering off, miserable and alone. These two new ones arrive at the same destination; but the journeys are very different. In the performance from Chicago, the direction, choreography and design are all by one man, John Neumeier. Orphée is a choreographer, Eurydice a star ballerina. During the Overture, while Orphée is rehearsing the company, they quarrel: Eurydice storms out and is killed in a car accident. Consoled by Amour, his assistant, who shows him a painting of the underworld, Orphée imagines that he descends to Hades to rescue his wife. His sanity restored, he returns to rehearsing his ballet but at the end is alone, holding Eurydice’s veil. The Chicago production comprises Gluck’s Paris version, complete but for three of the dances at the end, and with a tenor Orphée. Aurélien Bory’s production from Paris, while lacking a comparable conceit, is in some ways more radical. Bory uses an optical device called Pepper’s Ghost, which teases and confuses the eye by altering the perspective so that characters sometimes appear to be pinned to the stage wall. And Raphaël Pichon has chosen Berlioz’s adaptation of 1859 for Pauline Viardot, which is essentially Paris 1774 but with Orphée sung by a woman at the pitch of the original 1762 version for alto castrato. Moreover, Pichon has replaced the cheerful Overture with the penultimate number of Gluck’s ballet Don Juan. At the end, he cuts the trio ‘Tendre Amour’ – as Berlioz did – and ends the opera with the second choral lament from Act 1 and the ensuing Ritournelle, heavily accented. The lovers are nowhere to be seen and it’s Amour who stares out at us, looking downcast; all the final dances are omitted. Both productions work well, but questions remain. If Neumeier and Bory each wish to emphasise the seriousness of the story, why include the bravura tenor aria ‘L’espoir renaît dans mon âme’, which is so out of keeping with the rest of the opera and which might not even be by Gluck? And why does Pichon use Berlioz’s version anyway? Neither production takes the opportunity of reassigning ‘Cet asile aimable’ to a Blessed Spirit, as used to be done. It has often been pointed out that the Eurydice of Act 3 is a passionate woman, demanding her conjugal rights almost on the spot: the chaste happiness of her air in the Elysian Fields is quite out of character, and I find Pichon’s description of it as an expression of ‘melancholy and unease’ impossible to accept. In the Chicago production the chorus is invisible, but there are plenty of dancers onstage. Orphée gazes at a photo of Eurydice during ‘Objet de mon amour’, there are more images on the wall, and he hands out copies to the Furies. He clutches a pillow in his grief and clings to Eurydice’s scarf, with which he tries to strangle himself. During the Dance of the Furies he holds a copy of the music: a distancing device, perhaps, but oddly enough you can see that it’s a vocal score of the original Orfeo ed Euridice. Dmitry Korchak is no haute-contre but a robust, heroic tenor. Lauren Snouffer is suitably boyish as Amour: Neumeier says that he is in love with Orphée, but that is not apparent. Andriana Chuchman makes a fiery Eurydice. The choreography executed by the Joffrey Ballet is imaginative, and the chorus and orchestra – performing at present-day pitch – are excellent under the admirable conducting of Harry Bicket. The Ensemble Pygmalion, on period instruments, play a fraction lower. Here the chorus is onstage. Marianne Crebassa, in a trouser suit and a grey wig that gives her a startling resemblance to Julian Assange, is magnificent. She delivers both ‘Laissez-vous toucher par mes pleurs’ and ‘Quel nouveau ciel’ perfectly still, straight to camera. The coloratura of ‘L’espoir renaît dans mon âme’ goes with a swing, but I wish we were spared the ghastly cadenza from Pauline Viardot’s own copy. Cupid in a pink dress is hard to take, but Lea Desandre is good in a portrayal less skittish than usual. Hélène Guilmette, too, is good at expressing Eurydice’s lack of understanding. Raphaël Pichon and his chorus and orchestra are exemplary. Both productions are clever and enjoyable. In the end, though, why don’t these unhappy producers stick to what Gluck wrote? With its jubilant chorus and verses for each of the soloists, the ending is Imaginative choreography: Chicago Lyric Opera present the Paris version of Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice not as perfunctory as some make out. The original myth has Orpheus torn to pieces by Maenads, his severed head floating – still singing – down the river Hebrus. No 18th-century composer would have set that. Instead, Gluck and his librettist end with ‘L’Amour triomphe’. Is that so problematic an affirmation? |

|||||||