Reviewer: William

J.Gatens

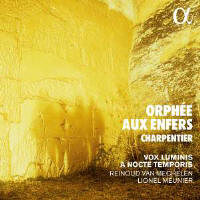

Marc-Antoine Charpentier

(1643-1704) is best known for his sacred music, much of it written in the

1680s for the private chapel of the Duchess of Guise in Paris. These two

pieces based on the Orpheus legend are examples of secular music produced

for her musical establishment. The earlier piece, written in 1684, is the

chamber cantata Orpheus Descending into Hell (H 471) for three voices,

recorder, transverse flute, two violins, and continuo. It presents a

vignette from the legend. Orpheus journeys through the underworld singing a

lament for Eurydice. He encounters Tantalus and Ixion, who feel their

infernal tortures mitigated by the sound of his song. As Vincent Borel

points out in his notes, Charpentier’s work displays the influence of his

studies with Giacomo Carissimi in Rome and his exposure to Italian dramatic

composition at that time. In contrast with the formal

recitative-air-recitative-air structure typical of the French chamber

cantata of the late 17th and early 18th Centuries, Charpentier delves into

the dramatic character of the brief episode. The boundaries between

recitative and lyrical idioms are not as sharply drawn as we might expect,

so that recitatives take on the character of declamatory arioso comparable

to liturgical settings of the Tenebrae Lessons by Charpentier and others,

while the lyrical idiom seems less bound to formulaic structures. This

produces a fluid continuity as the music passes from one to the other.

The other piece, Orpheus’s Descent into Hell (H 488), first

performed in 1687 at the Guise mansion in Paris, is a miniature opera. Two

of its three acts survive. It has a larger instrumental ensemble and cast of

characters than H 471, including a chorus of nymphs and shepherds in Act I

and a chorus of shades and furies in Act II. Act I begins with arcadian

revels in honor of the marriage of Orpheus to Eurydice until she is bitten

by the serpent and dies. Orpheus enters as she is expiring and is

devastated. He wants to take his own life, but Apollo persuades him to seek

Eurydice in the underworld. Act II takes place in the underworld. As in H

471, Orpheus encounters the shades of Ixion and Tantalus, here augmented by

the shade of Tityus to form a mellifluous male-voice trio. As in the earlier

cantata, they derive comfort from Orpheus’s song. At length Orpheus comes

into the presence of Pluto, who threatens him. Orpheus pleads his case,

Proserpina is touched, and eventually Pluto relents, allowing Orpheus and

Eurydice to return to the living on the condition that Orpheus not turn to

look on her during the journey. The act concludes with serene choruses of

shades and furies and a gentle instrumental symphony.

Notations in the manuscript indicate that the piece was staged.

From 1672 until he died, Jean-Baptiste Lully was director of the Academie

Royale de Musique, and that gave him complete control of opera in Paris.

Operatic productions under any other auspices were banned. Perhaps it was

only because the Duchess of Guise was a member of the royal family and was

presenting Orpheus’s Descent

into Hell

at her private residence that

Lully was unable to quash the production. That was the year that Lully died.

Charpentier wrote several operas afterwards, most notably Medée

(1693). It was not a popular success at the time, but it is now regarded as

one of the outstanding works of French lyric tragedy. At least five of his

operas are lost.

In this performance both Lionel Meunier and Reinoud van Mechelen

are credited as musical directors. Both also perform as singers: Van

Mechelen (haute contre) as Orpheus in both works and Meunier (baritone) as

Tantalus in H 471 and Apollo and Tityus in H 488. The performance standard

is first rate. The singers have light but substantial voices as befits this

repertory. Both singers and players

perform this music as if it is

their native language. The recorded sound is warm and clear, but as I find

with so many recent recordings of early music, it is excessively close.

Sometimes I can hear the breathing of the director. The lack of aural space

can be stifling, analogous to viewing a large mural while constrained

to stand no more than 20

inches from the wall. Levels are high, almost to the point of distortion.

Turning down the playback volume helps, but the sound still seems too close.

It is hard to find fault with the performance itself. My one

complaint is that the harpsichord continuo is prominent to the point of

distraction. Some of this may be from the too-close recording, but the

realization itself seems too busy to me, though I have heard worse. Continuo

should supply an unobtrusive support to the solo voices and instruments

without attracting undue attention to itself. It is worth noting that organ

and theorbo also appear as continuo harmony instruments, and the contrasts

in color and character are highly effective.

In these two works Charpentier displays himself as a master of

dramatic composition and pacing. In this recording the pluses far outweigh

the minuses. I commend it to anyone wishing to make the acquaintance of

these two remarkable works. As for earlier recordings of H 488, Gil French

had good things to say about the one directed by William Christie (Erato;

M/J 1997), and John Barker had compliments for recordings by Paul O’Dette

and Stephen Stubbs (CPO 777 876; S/O 2014) and by Sebastien Daucé (HM

902247; N/D 2017).

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

|