Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: Alpha |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Charles

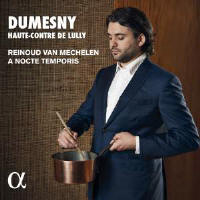

Brewer There have been recordings dedicated to the vocal repertoire of castratos such as Carestini (Erato 95242), Senesino (M/A 2006: 229), and the most renowned, Farinelli (M/J 1996: 256, S/O 2002: 227, M/J 2017: 191). This is the first recording I know of devoted to a specific French singer of the baroque, Louis Gaulard Dumesny (c.1635-1702). It is titled “Dumesny: Haute-Contre de Lully”. The French haute-contre was a natural male voice that was equal in tessitura to a female contralto—not a falsettist as understood by the modern usage of “countertenor”. In the manuscript of the “Histoire de l’Académie royale de musique depuis son établissement jusqu’à présent”, written by the brothers François and Claude Parfaict in 1741, Dumesny was described as a “haute-taille, des plus hautes” (a high tenor, among the highest). He was a cook whose talent was discovered and developed by Jean-Baptiste Lully even though Dumesny never learned to read music. Starting with smaller roles, he eventually became the most important male singer in the later 17th Century. Following his performance as the lead in Lully’s Phaeton in 1683, the popular press included a short distich, “Ah, Phaeton, est-il possible/ Que vous ayez fait du bouillon?” (Ah, Phaeton, is it possible that you once made broth?). Dumesny sang in the premieres and revivals of more than 30 tragedies lyriques. This collection begins with excerpts of the airs sung by Dumesny in Lully’s Persée (1682), Amadis (1684), and Armide (1686). Lully did not write expansive solo arias, so these are mostly short lyrical moments removed from their dramatic context. Following Lully’s death and the ending of his monopoly on the composition of tragedies lyriques, Dumesny continued to sing for a number of creative composers, including Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704), Pascal Collasse (1649-1709), Marin Marais (1656-1728), André Campra (1660-1744), Henry Desmarest (1661-1741), Elizabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1729), Charles-Hubert Gervais (1671-1744), and André Cardinal Destouches (1672-1749). Many of these composers had more freedom to write expansively for the voice, and the excerpt from Marais’s only tragedie lyrique, Alcide (1693), ‘Ne pourrais-je trouver de remède à ma peine?’ (Can I find no remedy for my pain?), is particularly effective. Though Lully had supplied the model for the ‘Sommeil’ (sleep or dream scene), the later examples included on this release from Desmarest’s Circé (1694) and Campra’s L’Europe Galante (1697) are much more subtle.

Reinoud van Mechelen is to be commended for performing this repertoire, including excerpts from larger works that have not yet had complete recordings. For the most part, his voice fits this repertoire quite well, though even at the lower French baroque pitch (about a whole tone lower than A=440) he occasionally has to force his vocal production when the tessitura becomes too high. To be fair, even Dumesny was sometimes accused that “he sang out of tune”. Van Mechelen’s direction of the excellent ensemble is also quite stylish and demonstrates an intimacy of interpretation not always evident in video recordings made from concert productions.

Texts

and translations.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|