Reviewer: Willian

J. Gatens

The office of Matins is

ordinarily sung in three nocturns through the night, culminating in the

office of Lauds at daybreak. In the Sacred Triduum of Holy Week (Maundy

Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday) it was the custom in many places

to advance the office to the early evening of the preceding day and to

observe it with solemn polyphonic settings of the lessons and responsories.

The office came to be known as Tenebrae. The music recorded here is for the

first nocturn of each day, with lessons from the Lamentations of Jeremiah,

including the headings that introduce the lessons, the Hebrew initials that

stand at the heads of the verses, and the refrain, “Jerusalem, Jerusalem,

convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum”, which concludes each lesson.

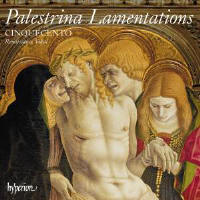

In 1588 Palestrina published a set of Tenebrae lessons that has since come

to be known as Book 1. The music recorded here dates from some 30 years

earlier, when the composer was choirmaster at the Basilica of St John

Lateran. The primary source for this music is Lateran Codex 59, published in

the 19th Century by Pietro Alfieri. There are at least two other sets of

lessons reliably attributed to Palestrina and a third that is doubtful. As a

practical liturgical setting, the lessons of Book 2 cover a great deal of

text in settings that are concise but never sound rushed or compressed. They

project a somber sublimity and eloquence that help to explain why Palestrina

was so widely regarded as the ultimate exemplar of the vocal polyphonic

idiom.

The music is sung one voice to a part by the ensemble Cinquecento,

a group of five singers from Austria, Belgium, England, Germany, and

Switzerland. As Bruno Turner points out in his notes, this is the way the

music would have been performed in the papal chapels and many other Roman

churches in Palestrina’s day. The individual movements range from three to

eight parts, so three additional singers are involved. I would describe the

vocal tone as slightly reedy and well suited to the clear delineation of

contrapuntal lines. Most impressive is the excellent sense of phrase that

makes the music cohere without exaggerated dynamic contrasts. There are

dynamic inflections that help to shape the performances, but not so as to

compromise the quiet solemnity of the occasion. These are profoundly

expressive readings, not the dispassionate take-it-orleave-it approach we

hear too often. No one could ask for more technically polished singing.

Listeners attracted to this repertory will not go wrong with this.

The booklet gives full texts and translations. The track list

specifies which singers are performing what. As we have come to expect from

Hyperion, the recorded sound is very attractive: clear but with a warm

reverberation.

Fermer la fenêtre/Close window

|