Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: |

|

|

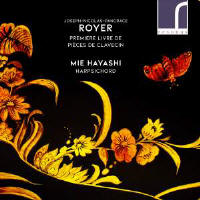

Reviewer: Bertil

van Boer

For composers living in France

during the first half of the 18th century, there must have been considerable

pressure to live up to the keyboard pieces or books published by François

Couperin (also reviewed in this issue). These were intellectual exercises,

most of them, with the intent of providing a civilized society with a set of

social music that demonstrated ability, as well as contained allusions to

various things. These books were filled with titled works, generally with

the notion that the performers would delight in the subtle twists and turns,

an effort that, if successful, would earn them a reputation both for their

theoretical skill as well as their popular content. One can be reminded of

Jean-Philippe Rameau, whose Pièces de clavecin from 1724 onwards established

him as one of the foremost followers or successors to the aging Couperin.

Few, however, have probably ever heard of Joseph-Nicholas-Pancrace Royer

(1703–1755). The son of a Savoy military man, he came to Paris at an early

age, where he first began a career as an administrator at the Opéra, and

then in 1748 led the famed Concerts spirituels. He also taught members of

the court of Louis XV, and he was known primarily for his various theater

works, especially the ballets de cour. Given his stature in Paris as a

musician, he was probably destined to publish this volume of pieces, meant

mainly for the well-heeled amateurs of the time.

One oddity is that he uses no

fewer than six different clefs, possibly to add an additional challenge to

his would-be performers. The movements are titled, giving them a slightly

old-fashioned, Couperinesque feel. They range in style from simple and

naïve, such as “La bagatelle,” which he then turns into a minor key

variation entitled “suite.” “Le vertigo” is a rondeau that teeters and

totters about various keys, suddenly falling precipitously down a scale or

arpeggio. Nothing is stable, either melodically or harmonically, lending it

a sort of air of a fantasy. There is even a rather manic moment in which the

keyboard is mechanically pounded, but ending in a whirling froth. “Le Zaïde”

is a tender and quite languid piece, clearly a characterization based upon

some stage persona. The set ends with a Scythian march, a harmonically

bizarre movement that wanders about with some chromatic passagework and a

monotonous main theme. A final flourish that stops abruptly and with

swishing patterns returns back to the mincing main theme. The harpsichord is a modern copy by Andrew Garlick of a 1749 Goujon, just the sort of instrument that would have been used in Paris. The sound is robust and pointed, and harpsichordist Mie Hayashi does an absolutely outstanding job of performance. She knows instinctively how to phrase the often gnarly passagework that Royer demands, making it exciting and musical, rather than just an intellectual exercise. There is a base canard that all French harpsichord music after the death of Couperin was nothing but a pale imitation. This fine recording should put that idea to rest. Highly recommended.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|