Texte paru dans: / Appeared in: Hyperion |

|

|

Outil de traduction ~ (Très approximatif) |

|

|

Reviewer: Rob

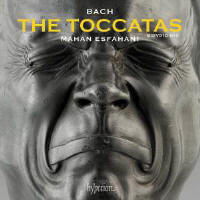

Haskins When a pianist or harpsichordist performs one of the Toccatas, he is probably aware that these are early works—at the very least, he would know that it is very much unlike works like the WTC or the Partitas. So then, the vexing question: how should one play Bach’s early harpsi-chord music? In the many releases of the Toccatas I have reviewed, performers— especially pianists—seem to treat them as early, immature works—more diverting oddities unlike the great works that Bach would later compose. Evan Shinners falls into this lamentable category (J/A 2013). Even with harpsichordists who are aware of the stylus phantasticus style of 17th Century music on which Bach probably modeled the pieces, the results are, more or less, a superficial, surface-oriented approach to the toccatas’ untamed excesses. Two exceptions among others: Anthony Newman on Vox (S/O 1996) and Peter Watchorn (N/D 2000).

Mahan Esfahani offers a wide-ranging, historically informed answer to this question that I find extremely attractive and convincing. After a thorough investigation of the numerous sources for these works he makes an extraordinary, but to my mind commonsensical, claim: there is in fact no “authentic” way of performing the works; rather, they

seem to invite, perhaps more

than s me of his other works, what he calls a “dialogic” relationship

between performer and text, one that elevates the former to something much

like a co-creator.

Another important context for

these pieces emerges more clearly in the playing itself rather than from the

essay: the great organ fantasies and toccatas with which Bach would dazzle

audiences for decades. He does this in part with his choice of instrument by

Jukka Ollikka of Prague; it follows theories and surviving examples of

Michael Mietke’s instruments, including what Esfahani calls “the

hypothetical addition of an extra soundboard for the 16’ register and a

cheek inspired by Pleyel, 1912. The instrument is over 9 feet long, had a

wide range, and includes registers of 16’, two 8’, and 4’ with buff on the

upper manual. Finally, the soundboard is made from a carbon-fiber. With this

instrument, Esfahani easily captures the grand sonorities of the organo

pleno if not all of its most colorful solo stops. The two 8’ courses are

very colorful and tender, quite powerful when coupled, the 4’ brilliant but

unobtrusive, and the 16’ (which is used often) extremely robust.

| |

|

|

|

|

Cliquez l'un ou l'autre

bouton pour découvrir bien d'autres critiques de CD |

|