Texte paru dans: / Appeared in:

|

|||||||

|

Outil de traduction (Très approximatif) |

|||||||

|

Reviewer:

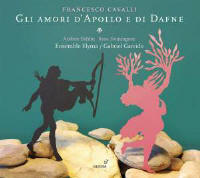

Tim Ashley Released in the last couple of months, this striking pair of Cavalli recordings were both actually made more than a decade ago. Marking the work’s first appearance on disc, Channel Classics gives us Mike Fentross and La Sfera Armoniosa’s L’Ipermestra, recorded live at the opera’s first modern performance, in Utrecht during the 2006 Holland Early Music Festival. Glossa, meanwhile, has reissued Gabriel Garrido’s 2008 Ensemble Elyma recording of Gli amori d’Apollo e di Dafne, originally released on the French K617 label, though not reviewed in these pages at the time. L’Ipermestra was first performed in Florence in 1658 to celebrate the birth of the first son of Phillip IV of Spain. The subject, which ostensibly sits uneasily with the circumstances of the premiere (though the underlying theme is the need for dynastic preservation), is a variant on the myth of the Danaïdes, the 50 daughters of the Argive king Danaus, married to their cousins, the 50 sons of King Aegyptus of Egypt, 49 of whom were murdered by their wives on their wedding nights at Danaus’s insistence, after an oracle prophesied he would meet his death at the hands of one of his nephews. Only Ipermestra, in love with her husband Linceo, refuses to take part in this bloodbath, and engineers his escape, to her father’s fury. Back in Egypt, however, Linceo is conned by Danaus’s general Arbante, who loves Ipermestra himself, into believing her unfaithful, and Argos and Egypt are soon at war. When Glyndebourne staged the opera two years ago, many commented that the proportion of recitative to aria or arioso was excessively high, which sidesteps the subtlety of Cavalli’s methodology. Despite the ostensibly happy ending, and the comedic interjections of Ipermestra’s nurse Berenice (six times married and now looking for husband number seven), L’Ipermestra’s dramaturgy is rooted in classical tragedy and therefore dependent on declamation for much of its effect. It is the flexibility of Cavalli’s recitatives, frequently veering towards the grander contours of melody in a quest for psychological veracity, that gives the work its often hypnotic force. Fentross’s performance is superb, though some, I suspect, might find it eccentric. The realisation is his own, undertaken in collaboration with the organist Jolando Scarpa, and the results are unusual. A sackbut as well as low strings pick out Cavalli’s bass lines, which adds an extraordinary sombreness of tone to the whole enterprise. Fentross’s conducting is swift and urgent, allowing the big confrontations to register with great immediacy. Some of the voices are perhaps bigger than we usually find in Baroque music. Mark Tucker’s Arbante, in particular, sounds dark and weighty, if suitably obsessive and pressurising. Elena Monti really gets inside Ipermestra’s conflict between love for Emanuela Galli’s warm-voiced Linceo and filial duty towards Sergio Foresti’s overbearing Danao. Marcel Beekman makes a camp, funny Berenice, and Gaëlle Le Roi is touching as Elisa, Ipermestra’s lady-in-waiting and Arbante’s much-put-upon ex. It’s a fine achievement. There is, however, one maddening drawback in that the accompanying booklet only gives us the libretto in Italian, a problem that also besets Garrido’s Gli amori. The work itself was first performed in Venice in 1640. Giovanni Busanello’s erudite libretto derives from Ovid, weaving together multiple tales from the Metamorphoses to form a complex disquisition on the nature of desire and its attendant catastrophes. The story of Apollo’s unrequited love for Daphne forms the kernel of the plot, though twining its way in and out of the main narrative is a counterplot dealing with the goddess Aurora’s affair with the mortal Cefalo, to the ignorance of her husband Tithonus and the horror of his wife Procris, whose anguished lament forms a real heart of darkness at the centre of a score that is otherwise often strikingly erotic. Garrido captures both its sensual mood and dark undertones wonderfully well, though he can be fractionally too languid and could do, on occasion, with some of Fentross’s impetuosity. It’s finely played and for the most part beautifully sung. Rosa Domínguez’s Dafne fends off the attentions of Anders Dahlin’s handsome-sounding Apollo with assertive dignity. Galli, the only singer common to both sets, is the persuasive, beguiling Aurora, and her scenes with Stephan Van Dyck’s bewildered yet enraptured Cefalo really do send shivers down your spine. At the centre of it all, Marisú Pavón sings Procris’s lament with a quiet intensity that resonates down through the rest of the work. It’s another fine set, and if you care remotely for Cavalli you should hear it, along with Fentross’s L’Ipermestra. In both cases, however, the absence of translations is a real pain, and regrettably there seem to be no English versions of either opera online. |

|||||||